|

the

Atlantic Strikes Back

During the five years of Raymond Orteig’s challenge,

there were no serious contenders for the

prize, so he renewed the

challenge for another five years. The first

serious entrants into the

contest (fliers wishing to be

considered had to first register with the Aero Club of

America) were, as Orteig

had hoped, French. Two veterans of

the war wounded in action, French ace Paul

Tarascon and François Coli, outfitted a Poletz

biplane for the flight during the

summer of 1925.

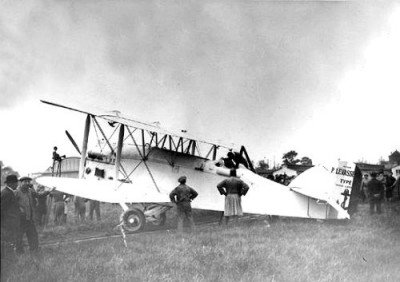

The ill-fated Sikorsky S-35 at Curtiss Field, 1926

They planned to drop the wheeled

undercarriage after taking off and

land on skids on a golf course in

Rye, just north of New York City.

Racing against them was another French

team flying a Farman

Goliath bomber that had set an

endurance record of forty hours in the air. The Poletz,

trying to duplicate the endurance record of the

Goliath, crashed and exploded; the

crew just barely escaped with

their lives. In the United

States, a captain of the Air Service

Reserve, Homer M. Berry,

decided he would take a crack at

the prize, and he organized a company for that purpose,

Argonauts, Inc., with the help of New Hampshire

paper magnate Robert Jackson. Berry

and Jackson then contracted

with the recent émigré Igor Sikorsky to build a

plane that could make the

trans-Atlantic flight.

Fonck was frequently photographed in

the cockpit

of the S-35 wearing anything but flying togs.

Sikorsky had just fled the Russian

Revolution and, with the help of

some illustrious refugees (like Sergei Rachmaninoff),

was establishing an aircraft manufacturing

business on American soil.

By the end of 1925, Sikorsky had constructed for the

Argonauts the S-35, a huge biplane

with a 101-foot (31m) wingspan and

weighing nine tons (8t) when fully

fuelled (but without crew and cargo); it was

at first powered by two Liberty engines, then by

three Gnome-Rhone Jupiter 450-hp

engines.

Sikorsky built and

serviced the plane—now named New

York-Paris—at Roosevelt Field on Long Island,

New York, and all of New York (it seemed),

including the flamboyant

mayor, Jimmy Walker came out to

watch the plane put through its

paces. Berry no doubt thought

that he would pilot the plane, but late in 1925 the

legendary French ace René

Fonck visited the hangar where the

S-35 was being built.

The favourites to win the Orteig Prize in

1926 were Igor Sikorsky

(far left) and Captain René Fonck (far right), who are

seen

here being visited by the

assistant secretaries of war,

Trubie Danison and (to his left) William McCracke

He made it clear to the

Argonauts that he would welcome an invitation to fly

the plane, and the Argonauts

happily obliged, making Berry

the co-pilot. Fonck made all sorts of demands on the

design of the plane itself,

including insisting that the

fifteen-foot (4.5m) cabin be decorated in red satin, gold

fittings, and mahogany and

leather panelling. All this irked

Sikorsky, who was depending on the S-35 to

make his reputation, but Fonck,

aside from being a hero of the war, had been instrumental in

procuring the Jupiter engines. The crew had grown to five,

and at the last minute Berry was forced out in favour of a

navigator supplied by the U.S. Navy. Finally, after

anticipation had risen to a fever pitch, the date for the

take-off was set for September 21, 1926, if weather

permitted.

Thousands of New Yorkers lined the field

to witness this historic moment. Fonck led the grand

procession to the plane, and all the crew had baggage and

gifts loaded onto the plane. Fonck was given a basket of

croissants by Orteig, which he cheerfully tossed into the

cabin. Sikorsky watched nervously and estimated that the

gross weight of the plane was well over fourteen tons

(12.5t)—more than ten thousand pounds (4,540kg) over

specifications.

The S-35 was among the most advanced

aircraft of its day, and in

the opinion of most experts would

be able to make the

trans-Atlantic flight to Paris with little difficulty. And

yet....

Later there would be some question

whether Sikorsky said anything to

Fonck, but at the time it probably

would not have mattered. Fonck and

the others were completely caught

up in the moment.

During take-off, a wheel on the undercarriage came

loose when the plane passed over a

rough service road that

crossed the runway. Jacob Islamov, a friend of

Sikorsky and the plane’s

mechanic, was in charge of

releasing part of the landing gear once the plane was

airborne (to reduce the load).

Thinking the entire plane would

roll over, Islamov released the landing gear,

sending the plane hurtling over the hill at the end

of the runway. The crowd watched

in horror as the plane

disappeared silently over the hill; then a great

explosion erupted and shook the

ground and lit up the sky.

Sikorsky ran the length of the field and found Fonck

and another crewman crawling away from

the burning wreckage;

Islamov and the radio man were trapped

inside. Fonck stood dazed,

watching the fire and the frantic, but futile, efforts of

rescuers. “It is the fortunes of the

air,” he pronounced, and

Sikorsky eyed him poisonously. At

the inquest, Fonck was accused by many

(including, naturally,

Berry) of not being competent to fly so large a

plane and of not aborting the

take-off when the wheel fell

off.

Sikorsky was mildly reprimanded for not carrying

out the complete regimen of

flight tests with full loads

(though the problem, it was determined, had not

been with the plane, but

with the runway and undercarriage),

and the navy man, a former aide to

Admiral Moffett, vouched

for Fonck’s abilities. The coroner, possibly bowing to

political pressure, exonerated

Fonck and ruled the crash “an

unfortunate accident.” Most amazing of all,

perhaps, is that after

the inquest Sikorsky and Fonck

announced that they would build a

new plane and try again the next

year.

The S-35 was only the first casualty to be claimed by the

Atlantic; before Lindbergh’s

flight, there would be others.

Following his successful flight over the North Pole,

Richard Byrd persuaded a

young Norwegian flier, Bernt

Balchen, to join him, Floyd

Bennett, and George Noville, as a

ground-crew member in an

attempt to cross the Atlantic.

Byrd placed his plane, the

Josephine Ford, on display

in department stores owned by

Rodman Wanamaker, which led to

Wanamaker’s enthusiastic backing

of the trans-Atlantic flight. Byrd

ordered a new Fokker

Trimotor, and Wanamaker

sentimentally named it the America

(after the Curtiss boat

plane he financed before the war for a trans-Atlantic

flight). During a test flight in Teterboro, New Jersey, with

Fokker himself at the controls and the three crew members

aboard, the plane flipped over during landing. Byrd

had a broken arm, Bennett a fractured leg, and Noville was

most seriously hurt with internal injuries; only Anthony

Fokker walked away from the crash unhurt.

Seen here in 1926 is Floyd Bennett, pilot

of Commander Richard E. Byrd’s

Josephine Ford,

a Fokker triplane, which flew over the North

Pole.

The flight of the

America would be delayed until craft and crew mended.

Another entrant was Noel Davis, commander of the Naval

Reserve Station in Boston, who had tried to get support

since 1925 for a try at the Orteig prize. In January 1927,

he filed that he would be flying a tri- motor manufactured by

the Keystone Aircraft Corporation. Keystone called the model

the Pathfinder (only one was built), but he called the plane

the American Legion because most of the funding was coming

from the Legion, which hoped that a successful flight would

publicize the convention it was having in Paris that summer.

During trials out of Langley Field, Virginia, in April 1927,

the plane lost power and dove into a marsh, killing Davis

and Stanton Wooster, his co-pilot.

Meanwhile, the French made

another attempt at the prize. Charles Nungesser, France’s

second highest ranked war ace (second only to Fonck, and

considered a better flier), teamed up with Francois Coli and

the two prevailed upon the airplane builder Pierre Levasseur

(of Antoinette fame) to equip a plane he was building for

the French Navy for a trans-Atlantic flight.

Levasseur PL 8

The plane, the

PL-8, was an open-cockpit biplane with a detachable

undercarriage and a watertight fuselage that could float on

water. It was Nungesser’s plan to eject the undercarriage

after takeoff and land in New York Harbour on the

fuselage. Nungesser painted the plane white and called it

L’Oiseau Blanc (The White Bird), putting his trademark

skull-and-crossbones-in-a-black-heart emblem on the side of

the plane.

Charles Nungesser, heroic aviator of World

War I, was

known as the “Prince of Pilots.” His disappearance over the

Atlantic

was a tragedy that was deeply felt by the entire aviation

community.

Nungesser and Coli took

off from Le Bourget Field (they claimed they were flying the

more difficult east-west direction out of patriotism, but

the simple fact was that they had no money to transport the

plane to New York) on May 8, 1927, Joan of Arc Day and the

anniversary of the beginning of the flight of the NC boats.

Candles were lit all over France and prayers were uttered in

churches as the entire nation turned out to watch the plane

fly over the coast of Normandy toward America.

The weather reports were

discouraging—at Roosevelt Field, Clarence Chamberlin,

engineer of the Wright engines, heard reports of Nungesser’s

takeoff and of the weather over the Atlantic, and muttered,

“I don’t see how Nungesser can make it.” A report was sent

to Paris, resulting in a detailed front-page story, that

Nungesser and Coli had landed safely near the Statue of

Liberty. France erupted in joyous celebration, but the

report proved false, which made the later disappointment

even greater. The White Bird was never seen again, and it

was all the U.S. State Department could do to dispel rumours

that American weatherman had withheld weather information

that would have delayed the flight. No part of the wreckage

of the White Bird has ever been found.

The deaths did not end

even after Lindbergh’s flight in May 1927. Before the end of

the year, three other planes set out to cross the Atlantic

and did not make it. The first, an east-west flight in a

single engine Fokker called the St. Raphael, took off from

England on August 31, bound for Ottawa. The plane was

piloted by two experienced RAF pilots, Leslie Hamilton and

Fred Minchin, and had an illustrious passenger: Princess

Anne Lowenstein-Wertheim. Wertheim was well known as an

intrepid aviator with several records to her credit. She

kept her involvement in the flight secret (mainly because of

her aristocratic family’s objections to her flying career)

until just before boarding. The plane was spotted en route

by an oil tanker, and then disappeared into the Newfoundland

fog. For years, searchers combed the Canadian wilderness for

wreckage, but found nothing.

The Fokker F.VIIA "Old Glory" that James DeWitt Hill and

Lloyd Bertaud used for their attempted transatlantic flight

On September 6, a Fokker

single-engine called Old Glory took off from Old Orchard

Beach, Maine, for Rome, attempting the first nonstop

U.S.—Rome flight. The plane was sponsored by William

Randolph Hearst, who, ever sensitive to publicity, had

Philip Payne, editor of the New York Daily Mirror, one of

his newspapers, go along on the flight to drop a wreath over

the Atlantic that read, “Nungesser and Coli: You showed the

way. We followed. (Lloyd) Bertaud and Payne and (James D.)

Hill.” The next day, an SOS was received and rescue ships

raced to the spot 600 miles (960km) off the Newfoundland

coast. They found the plane bobbing in the water, but there

were no bodies and no indication of what had happened. Even

before the wreckage of the Old Glory was found, another

plane took off to cross the Atlantic, the Sir John Caning,

with a British crew of two.

It disappeared without a

trace over the Atlantic, without so much as an SOS. On

September 9, 1927, the U.S. Department of State and the

Navy, in response to public revulsion at all the lost

fliers, called a halt to further transoceanic attempts.

|