Benito

Mussolini had risen to lead Italy in 1922 by promising to restore its

ancient power and prestige. He planned that, while Britain concentrated

on defending itself against Hitler’s attempted invasion, Italy would

conquer its colonies in the Mediterranean, which Mussolini called mare

nostrum ("our sea"), beginning a new Roman Empire. Thus, the war in the

Mediterranean theatre took place on the deserts of North Africa, the

waters of the Mediterranean and the hills of Italy, and involved both

Italy and Germany.

When

Germany invaded Romania in 1940 without informing Italy, Mussolini felt

that Hitler was trying to keep south-eastern Europe for himself and

invaded Greece on October 28, 1940, to protect Italian interests. But

Italy lacked supplies and organization, and the action soon became a

humiliating failure. Hitler was forced to come to the rescue with a

full-scale invasion, delaying the invasion of Russia and using vital

troops and supplies. From mainland Greece, Germany captured Crete with

the largest airborne attack to date: more than 10,000 paratroops and 750

glider troops. A subsequent German attack on the island of Malta was not

successful, however, allowing the British air bases there to continue to

attack shipping and other naval activities in the Mediterranean for the

remainder of the war.

Hitler

also came to Italy’s aid against the British in North Africa, sending

tank divisions led by Field Marshall Erwin Rommel (sometimes known as

the "Desert Fox") in February 1941. For two years, the adversaries

fought on desert sand that shifted almost as much as the fortunes of the

armies. It was especially difficult for the air forces--the heat made

crews ill, sand destroyed engines, and metal became too hot to touch.

The theatre was nicknamed the "Battle of Airfields" because the strength

of each army was connected with its air force’s access to airfields. The

air power of an advancing army diminished as it had to use an unprepared

airfield while that of a retreating army increased as it fell back onto

a prepared one. And when the winter rains arrived, the most forward

armies lost their advantage, as unprepared airfields became mud pits.

On November 8, 1942, while

the Afrika Korps was retreating westward from Egypt, the Allies invaded

French West Africa in Operation TORCH.

The

air forces were overtaxed because they were given too many different

missions: ground support, navy support, defence of supply routes, and

attacking enemy supply routes. The loss of men and equipment was high.

The Luftwaffe pulled air groups out of the Russian campaign to help--a

costly mistake. And the Royal Air Force had planes, but many could not

fly due to maintenance problems. Its special Maintenance Group was

created and assigned to maintain, repair, salvage, and store the

airplanes. This allowed the RAF to keep more planes flying, and after

several months, to maintain air superiority for most of the rest of the

campaign.

Despite the RAF’s air superiority, Rommel and his ground troops were

able to continue advancing across Africa. But the entrance of the

Americans into the war started to change the equation. They began to

arrive during the summer of 1942, primarily one small unit, the 57th

Fighter Group flying Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, which assisted with the push

into Libya. But President Franklin Roosevelt, eager to see his military

fight the Germans en masse, ignored his generals’ advice and planned a

massive North African invasion--Operation Torch. On November 8, 1942,

U.S. troops, with some British support, landed in Morocco. Although they

progressed rapidly, they were impeded by inter-Allied rivalries. During

a meeting in Casablanca in January 1943, British Prime Minister Winston

Churchill and Roosevelt were forced to organize the Mediterranean Air

Command, with RAF Air Chief Marshall Arthur W. Tedder in command.

British and American officers were interleaved down the command

structure, forcing international cooperation.

During

the winter of 1943-1944, in a project code-named "Ultra," the Allies

broke the Germans’ secret operational code. They could now detect

exactly when supplies were arriving and by which route, and could attack

the convoys. But they had to allow many to pass, careful that the

Germans not suspect their "luck" and suspect the code was broken. Not

until March 1943 were the air forces allowed to attack all convoys,

closing down Axis shipping completely.

On May

13, 1943, Tunisia fell and the Allies took 250,000 prisoners, most

German. And more importantly, they now controlled airfields that

airplanes could use to reach Italy. Reconnaissance units began

photographing Sicily to make photomaps for invasion troops. And General

Jimmy Doolittle and the Strategic Air Force (SAF) started bombing. The

SAF was able to inflict enough damage to reach the critical point where

German losses surpassed their replacement rate. In Sicily, the Luftwaffe

rapidly began to retreat. Reports claimed that German pilots were afraid

to attack the massed machine guns of the tight American bomber

formations. On hearing this, an incensed Hermann Goering demanded that

one pilot from each group be chosen randomly and court-martialled for

cowardice.

A Fleet Air Arm Martlet fighter from HMS Formidable patrols over the

veteran battleship HMS Warspite off Sicily.

The

invasion of Sicily began on July 9, 1943, with the 82nd Airborne’s first

mission. However, a storm that night scattered many airborne units,

making rallying difficult. And the next morning, the navy arrived with

ships of seasick amphibious troops. The invasion was marked by friendly

fire (firing on your own men), uncoordinated air support, lost troops,

and miscommunications. Yet by mid-August, the island fell, and 10,000

German and Italian troops fled over the Straits of Messina, untouched.

B-24s over Ploesti, with bombs

bursting on the target.

On

July 19 the SAF flew the first bombing mission to Rome. The targets were

two marshalling yards, and careful planning ensured that no cultural or

religious sites were hit. Pamphlets were dropped ahead of time warning

citizens to stay away. The raid was a success. A week later, Mussolini

was overthrown and Italy’s new leaders asked the Vatican to begin

inquiries regarding surrender.

Before

invading mainland Italy, the SAF was sent on the deadliest mission of

the war to the oil refineries of Ploesti, Romania, which supplied 35

percent of the oil used by Germany. To slip under the German air

defences, 176 B-24s bombers flew into Romania at a low altitude, making

them easy targets for anti-aircraft guns. Seventy-three airplanes were

lost, and 500 airmen were killed or injured. Five Medals of Honour were

awarded, the most for any single engagement during the war. But the raid

had no effect. The next summer, 20 missions were flown to Ploesti until

no oil refineries or anything else were left. The Allied toll for the

target was high--300 bombers, 200 fighters and over 1,000 airmen were

killed.

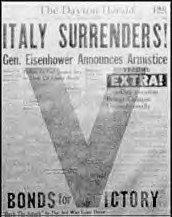

Italy's surrender was announced

on September 8, 1943.

On

September 8,1943, the same day that Italy’s surrender was announced,

Allied troops landed in Italy at Salerno and Bari. But the Germans were

still there, waiting for the troops. The air forces worked hard to

provide the Allied troops with air cover, while bombing strategic sites.

C-47s brought more paratroopers and P-51s helped direct naval

bombardments. But the ground troops were stuck at the Gustav line, a

heavily fortified and defended line across southern Italy, and a

miserable stalemate lasted through the winter. To break it, a second

landing was planned right above the Gustav line at Anzio on January 22,

1944. There, the Allies found Germans holding the high ground. It was

decided to starve the Germans out of the hills by bombing the supply

routes. By spring, the average German unit was reduced to 1,500 rounds

of ammunition a day, versus the 25,000 of their U.S. counterparts. But,

because they were unable to retreat after their fuel supply was cut off,

all the Germans could do was stay and fight to the death.

The

U.S. 15th Air Force in Italy was formed to operate strategic bombing

campaigns around Europe, such as at Romanian transportation hubs, French

harbours, Italian airfields and cities, and German factories. Although

less celebrated than its counterparts in England, the 15th flew longer

missions on average and aided in the final victory equally.

After

the Allies broke through the Gustav line in May 1944, the Germans formed

another defensive line along the southern edge of the Po River Valley

which they called the Gothic Line. But they were feeling the effects of

Operation Strangle, an attempt by the 15th to deprive the enemy of food,

weapons, or anything useful. In addition to the old targets, Allied

fighter-bombers now joined the action, strafing workers repairing the

bombing damage. By the time the Allies fought their way to the Gothic

Line in 1945, only one final assault was needed. On April 14, the

combined pressure of ground and air attacks sent the Germans running,

leaving their equipment behind. The Allies had defeated Italy. On May 2,

Germany surrendered and the war in Europe ended.