|

the

'wonder' weapons of Nazi Germany

an allied aerial shot of Peenemünde

Both the Allies and the Germans

invested large amounts of resources and funds inventing new

weapons. The most famous and effective wizard weapon was the

atomic bomb. Driven by a fear that Nazi Germany would

develop and use an atomic bomb first, physicist Albert

Einstein wrote President Roosevelt in 1939 to warn him of

the potential threat. US Army General Leslie Groves was

tasked with creating the American program, which used a mix

of eccentric academics and military spit-and-polish

officers.

Raids on the German heavy water plants in Norway indicated

that their program was behind the Americans, and emphasis

switched to using the bomb on Japan after the German

surrender.

The Germans were focusing on a number of weapons that were

retaliatory in nature. The V-weapons, or “vengeance”

weapons, were high-technology guided and unguided missiles:

the V-1 flying bomb began attacks on London and Antwerp,

Belgium in the summer and fall of 1944, after the Allied

landings. Randomly striking targets, the V-1s caused terror

out of proportion to their damage, but killed hundreds. Soon

the V-1s were supplemented with V-2 ballistic missiles, the

first true medium-range guided missile. Developed at the

Peenemünde missile complex, both missiles were soon out of

range of London as the Germans fell back to their own

borders. The V-3, a series of large guns built into the

French cliffs and aimed at London, was never completed.

Slave labour from the Nordhausen concentration camp was used

to build the vengeance weapons, resulting in thousands of

deaths from executions and starvations.

The other major German weapon was the Messerschmitt Me-262,

the world’s first operational jet fighter. In the space of

seven years, the world had gone from biplanes to jet

propulsion. Mounting 30mm cannon, it was a capable fighter,

but dangerous to the pilot if the fuel was not handled

carefully. Furious over bomber attacks on Germany, Hitler

ordered the aircraft to be used as a bomber, preventing its

defensive use and saving many Allied bombers. Rare metals

shortages grounded many planes. If the Me-262 had been

introduced a year earlier, the Allied strategic bombing

offensive would have been seriously compromised.

The Allies had very different opinions on the use of

technology. American combat doctrine called for very heavy

firepower to be used to smash a target, even if it could not

be seen. This was contrary to the basic combat instruction

that taught recruits to only fire at visible targets, but

the Americans eschewed most tactical technological

implementations. The British, however, developed many

operational weapons, most notably under the inventor Barnes

Wallis, who was an explosive expert. He developed the

’bouncing bomb’ that smashed Ruhr dams, and the ’tallboy’

and ’Grand Slam’ very large bombs that destroyed submarine

pens at Loríent and sank the battleship Tirpitz.

For the Normandy invasion, the British developed a number of

new technologies, including flail tanks that set off mines,

swimming dual-drive (DD) tanks, and carpet laying tanks.

Called ’Funnies’ these tanks were not used by the Americans,

except for the DD tanks. Other variants included the

Churchill Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers (AVRE) that

mounted a large mortar to assault concrete emplacements.

Major implementations of new technology at Normandy included

Pipe Line Under the Ocean (PLUTO) to provide the Allies with

enough gas, and the Mulberry Harbors, artificial breakwaters

Churchill insisted on building to facilitate landing men and

materiel.

By the time the Allies landed in France, the tide of

technological warfare had shifted to the Allies. Almost the

entire Allied air force were modern designs created in 1940

or after. The Germans were still using the same designs

created in the thirties. Also, the Germans developed several

types for each role, diminishing the effectiveness of their

armour and aircraft by making four or five types instead of

one or two.

Vergeltungswaffe-1 Attacks (the

V1)

By Raul Colon

September 24th 2008rcolonfrias@yahoo.com

During the wee hours of June 13th

1944 a sole Fieseler Fi-103 or V-1 pilotless bomb, rested on

its wheeled cradle at Hesdin in the Pas de Calais, ready for

takeoff. Its support crew, all members of Abteilung

Flakregiment 155; had worked relentlessly on the launching

platform during the past seven days.

In just a few more minutes they

would know if all of their collective efforts would be paid

off. They already had fuelled the missile and had rechecked

its navigational and electronic mechanisms. The only thing

left was the launch itself. Approximately at 3:49 AM, the

Flakregiment’s commanding officer, who sat in a reinforced

concrete Kommandostand (bunker), radioed the crew to

commence the firing sequence. Three minutes later, the roar

of the compressed air filtering into the 75 octane petro

chamber of the ARGUS pulse-jet engine began to engulf the

bunker. At the same time, a massive supply of air from two

parallel tanks on each side of the Fi-103’s launching ramp

was being diverted to a chemical combustion chamber.

As the gas mixed with the

chemical liquids, a violent reaction occurred propelling the

ramp’s firing piston forward taking with it the F1-103 at

nearly 250 miles per hour. As the missile began to slowly

pickup altitude, the launching crew cheered in unison.

Their week-long work had, not only paid off, but had been a

resounding success. Once the Fi-103 was airborne, the firing

squad watched in awe as the 103 climbed to a low angle as it

built up airspeed. Three minutes after the launch, the 103’s

navigational compass took over the missile steering. The

compass shifted, ever so slightly, the 103’s trajectory to

compensate for the forecasted headwinds. Three more minutes

passed and now the V-1 had achieved its expected cruising

altitude of 3000’. One minute later, the Fi-103 had crossed

the French coast heading for England.

Meanwhile, operators at the

British radar station in Swingate, near the Dover Straits

picked the faint signature signal of the now cruising V-1 at

around 4:02 AM. Four minutes later, spotters aboard a Royal

Navy torpedo boat patrolling the Straits picked up the

Fi-103’s silhouette.

They recorded the “sighting of

a bright horizontal flame” travelling north-westward from

the direction of Boulogne. Five minutes later, the Observer

Corps near Dymchurch saw an incoming “object” heading

northwest toward the English coast. Reports began to flood

in to headquarters and soon a code name was gave to the

incoming “pilotless airplane”: Driver. As Driver began to

move over the Kent countryside, spotters and radar stations

all across the V-1 path continued to report its trajectory.

At 4:20 AM, the Fi-103’s internal navigation system

automatically shut itself down at the preset coordinates.

Immediately, two electrical contacts closed the circuit

which fired a couple of detonators housed on the tail of the

craft in order to secure the V-1’s elevators and rudder in

the pre-arranged position. While this was happening, the

spoilers under the tail plane sprang out, thrusting the tail

structure upward thus forcing the missile into a steep dive

position.

The resulting negative G-forces

conveying on the platform pushed the remaining fuel to the

front of the pulse-engine storage tank, uncovering the feed

pipe forcing the pulse engine to flame out. After which, the

4858lb weapon plunged violently towards the ground. The

first V-1 crashed on to an open field area near Dartford, a

full fifteen miles from its intended target, Tower Bridge in

the centre of London. Three additional flying missiles would

be fired from northern France during a two and a half hour

period. Two of them crashed in open fields causing no

casualties or damage. The third plummeted onto Bethnal

Green killing six people and injuring ten more. Six

additional V-1s followed up the initial barrage, five of

them crashed into the Channel waters and one over Dover

itself without causing any damage. With these firings, the

long awaited “rocket” bombardment of England commenced.

The infamous Fieseler’s Fi-103

flying bomb was perhaps Nazi Germany’s main terror weapon

during that period of the war. Known as V-1 or Retaliation

Weapon Number 1, was in fact a first generation cruise

missile platform. It was powered by a powerful ARGUS pulse

jet engine which produced around 560lb thrust at a 400 miles

per hour. It had a wingspan of 17’-6”, length of 29’-1.5”

with a total wing area of 55 square feet. It carried a

1870lb warhead (there was an extended-range version of the

V-1 which carried a 1000lb) that detonated on impact. The

Fi-103 could travel up to 130 miles (extended version 200)

at an average top speed of 420 mph (480). Operational

ceiling was around 4000’. Total weight at takeoff was

4858lb. For guidance and navigation, the V-1 possessed a

rudimentary compass mechanism, an automatic pilot system and

an air log counter. The Fi-103’s airframe was a simple

structure. It had to be due to the massive shortages of

aluminum alloys inside the fast shrinking German Reich. The

system made its maiden flight in December 1942. The weapon’s

testing phase lasted until the next July when it was ordered

to into full production mode by an overstretched and

overmatched Luftwaffe.

When the Allied Army landed on

the Normandy beachheads on June 6th, the

Luftwaffe’s commanders, which along with most German senior

military leaders still believed that the main Allied attack

would come on the Pas le Calais, thought that all of the

newly built V-1 launching platforms would almost certain be

lost before they were to become fully operational to the

advancing allies invading force. As the landings were taking

place, Flakregiment 155 received orders from Berlin to

commence the planned massive bombardment of the British

capital. The June 13th would only be the first

salvo in a powerful missile barrage planned against London.

Following this up was an incredible work schedule, under

constant duress from allied bombing and strafing.

By the 15th

Flakregiment 155 was able to have all of its assigned Fi-103

launching platforms in the Calais area operational.

Commencing on the afternoon of the 15th until

midnight of the 16th, Flakregiment 155 launched

244 Fi-103s. Of the 244, 45 units either failed to make it

from their launching pads or crashed soon afterwards. Forty

units, which managed to clear the pad area, crashed into the

sea soon after takeoff. Only 153 units were able to cross

into British territory. Waiting for them were the newly

deployed anti-aircraft artillery pieces and recently formed

dedicated fighter squadrons, all stationed on the south

Great Britain in preparations to meet this improvised German

terror weapon. This screen of guns and aircraft were able to

shoot down twenty two V-1s. Of the remainder of the striking

force, fifty units crashed onto open fields across the south

of England without causing any damage. Unfortunately,

seventy three Fi-103s did find their marks and crash landed

in downtown London causing loss of life and severe

structural damage.

For the next fifteen days,

Flakregiment 155 launched 2442 flying bombs against the

beleaguered English capital. Of this impressive total, only

about 810 were able to reach their target. The rest were

either shot down during their trajectory or they simply

malfunctioned while in launching mode. The June 1944 Fi-103

barrage killed 2441 citizens while another 7107 were

seriously injured. Not all of the V-1 attacks were directed

at London. Few pre-programmed flying bomb were actually

targeted at military installations inside the Greater London

area. But, as with much of its conventional force, the

Fi-103 failed to make any significant dent in military

operations. This did not mean that it failed to cause havoc

on some installations. Such was the case on June 18th

when a sole flying bomb crashed on the Guard’s Chapel at the

Wellington Barracks. Sixty three soldiers and fifty eight

civilians who were attending the services perished in the

attack.

Because of the amount of flying

bombs being launched at Britain, its leaders re-directed

their air effort to look for and destroy all V-1 launching

sites near the Pas de Calais sector. Thus a new phase in the

ongoing air war above northern France began. Allied

reconnaissance aircraft were constantly on patrol looking

for V-1 launchers. Once detected, forward air controllers

would call in air strikes onto them. Unfortunately for the

allies, the Germans were by now versed in the art of

deception, thus most of their V-1 launchers were well

camouflaged. Nevertheless, allied aircraft did find some

sites and they were constantly bombarded. But the Germans

also proved very adept at rebuilding and soon, the attacked

sites were back in operation.

Post war German records tend to

support this claim. Of the 64 available sites, twenty two

were seriously damaged and 18 suffered medium damage. Of the

forty, only two sites were lost, the others were rebuilt and

back in operation within days. During the month of June,

twenty eight Germans were killed while working on the V-1

sites, a further 79 were injured. But while the allied air

attacks did not prevent the site from operating it did

hinder the Germans re-supply system. The already frail rail

and road system Flakregiment 155 utilized for weapon and

systems transportation was constantly attacked by allied

bombers affecting the interval time between V-1 launches.

Before the landings, the Luftwaffe had assigned a window of

thirty minutes between each flying bomb launch. Flakregiment

155 had reduced the lapse time to 25 minutes, but now, due

to the air harassing tactics of the allies, the interval

time climbed to 1.5 hours.

Notwithstanding the allied

strike campaign against the launching sites, the launches

continued almost unabated during the month of July. In fact,

during August 2nd, the 155 launched its most

massive attack so far. During a 24 hours window, the 155

launched 316 missiles at London. One hundred and seven of

them fond their target. In fact, three or five Fi-103s

crashed on the Tower Bridge damaging it. But by now the

German operations in the Calais area were fast coming to an

end. On the 7th, orders were issued to the 155 to

stop all repairs and new construction of Fi-103 facilities

south of the River Somme. Two weeks later, the whole German

Western front began to collapse. Flakregiment 155 began a

hastened eastward retreat leaving all of the V-1 sites open.

The last flying bomb launched from the Calais sector took

off on the 1st of September 1944.

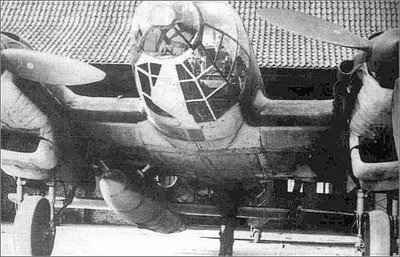

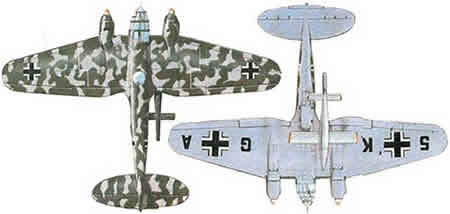

The situation on the ground

altered the German’s Fi-103 strategy. Since early July, III

Gruppe Kampfgeschwader 3 had joined Flakregiment 155 on the

bombing of London. Commanded by the famous Major Martin

Vetter, the Gruppe utilized a modified Heinkel He-111 heavy

bomber fitted with a special carrying device to launch the

V-1 missiles. The He-111 launched Fi-103 were modified from

the original version. These new flying bombs carried a

state-of-the-art FuG-101 Radio Altimeter and a

Lichetenstein’s Tail Warning Radar Array. As the four

engined bomber began to alter its flight pattern in order to

be able to deploy the new version of the 2.5 tons V-1

system. The He-111 was the long awaited hope for a by now

almost none-exiting Luftwaffe’s bomber arm. It was an

advanced four engine heavy bomber.

It was powered by two Daimer

Benz DB-610 engines generating each 2950 horse power. Each

DB-610 were complemented by two DB-605 engines attached

together while driving a single propeller alignment. This

arrangement gave the 111 a top speed of 270 mph at 20000’

with a cruising speed of 210 mph at 20000’. Operational

range was an impressive 3240 miles. The He-111 was a bulky

armed aircraft with no less than six gun emplacements

compromising of one MG-151 2cm cannon and one MG-81 7.9mm

heavy machine gun firing in the forward position (all from

the nose cone housing). Two MG-81 machine guns on the rear

fuselage. On each side, two heavy MG-151 machine guns. One

more 151 on a dorsal turret plus a MG-131 in the extreme

rear of the tail structure. The bomber was able to carry up

to 13200 pounds of ordinance in internal bomb bays plus,

either a Fritz X guide bomb or a Hs radio guided missile

system.

At least six crewmen were

needed to mange the aircraft in flight. The He-111 Fi-103

profile called for the bomber to cruise over at 170 mph at

an altitude not exceeding 300’. As they approach the

deployment area, the 111 turned into the target and

commenced to slowly climb to the safe deployment altitude of

1700’. When the He-111 reached the targeted altitude zone,

it levelled off at 200 mph. Before the bomb was deployed,

the crew started up the 103’s pulse engine for up to ten

seconds, this put in peril the aircraft’s ability to survive

the mission, before deploying the weapon. Once the V-1 was

dropped, it would fall for 300’ before the autopilot was

activated and began to correct the weapon’s course and

altitude. Meanwhile, the pilot and co-pilot of the 111 were

turning the big, lumbering bomber the other way in order to

escape the expected British fighters which would most likely

trace the muzzle signature of the deployed bomb.

From early July through the

first week of September, He-111s launched 300 flying bombs

at London, 90 at Southampton and a few to other population

centres. Then, on September 8th a new and more

terrifying weapon arrived over London, the vaunted A-4 (V-2)

ballistic missile. The rocket, which was fired from the

outskirts of The Hague, Holland; nearly 200 miles from the

British capital, made a lasting impression among its

citizens and their leaders who vowed to destroy the new

terror weapon.

From September 1944 through the

27th of March 1945, 1054 A-4 were launched

towards England. Of them, 517 hit London killing 2700 of its

citizens. Meanwhile, the use of the He-111 to deploy the V-1

flying bombs continued through the autumn and winter of

1944. Gruppe Kampfgeschwader 3 continued its assault on

Britain from bases at Aalhorn, Handorf-bei-Munster and other

facilities in northern Germany. Unfortunately for Germany,

the accuracy of these new airborne 103 was even worse that

the ground launched systems. Late in the autumn of 1944, and

newly re-formed Gruppen Kampfgeschwader 3 was joined by

converted Gruppen KG 53 for V-1 operations. But by this time

Germany was experiencing a huge petrol shortage which forced

the Luftwaffe to curb many offensive-types of operations.

Almost disregarding this fact, both Gruppens continued, but

at a more conservative pace, to launch V-1s towards London.

Although the British capital was the preferred target centre

for Luftwaffe’s commanders, there were other cities attacked

during the winter months. An example of one of those attacks

was Operation Martha.

Martha was a large group

bombing mission against the city of Manchester. On the

morning hours of December 24th 1944, fifty He-111

deployed their Fi-103s over the North Sea. Thirty V-1s

crossed the English coast at Bridlington then proceeded

westward. Of the thirty bombs, only one actually crashed in

downtown Manchester, fourteen others crashed in open fields

around the city. The unexpected attack forced the Royal Air

Force to re-deploy air defence assets to other locations

outside London. This was the last major operation of the

year. By January, the Gruppens combined strength was 79

He-111 from a preliminary force strength of 160 units.

Meanwhile, German engineers were feverishly working on an

extended-range version of the 103. One that could travel up

to 200 miles from its deployable bases. On March 3rd,

after nearly two months of lull in 103 launchings, the

Luftwaffe fired the first of 275 Fi-103 units launched

during the month. The longer range version proved even more

inconsistent and easy to destroy that previous system. The

greater distance provided the British with more

opportunities to shoot them down.

More than 10000 Fi-103 were

launched against Great Britain. Nearly 87 percent of them

were ground launched. Of the total number, 7488 were able to

reach the British coastline, 3957 of them were shot down

leaving 3531 flying bombs to pass through the British

defences. Of those that “got away”, 2419 crashed onto

London, 30 onto Southampton and Portsmouth while only one

reached Manchester. Total losses were 6184 killed and 17981

injured. Forgotten is the fact that there were other

countries attacked by the German’s V-1 weapon. On the 21st

of October, Fi-103 bombardment against allied positions in

Holland commenced. The attacks were concentrated against two

targets: the major port facility of Antwerp and Brussels.

Some 740 flying bombs were fired against the two cities. The

bombardment caused widespread damage to an already

structurally deficient infrastructure on both cities.

The Second World War: An illustrated History

of WWII, Sir John Mammerton,

Trident Press 2000

Air Power: The Men, Machines and Ideas that Revolutionized

War, Stephen Budiansky,

Penguin Group 2004

The Bomber War: The Allied Air Offensive Against Nazi

Germany, Robin Neillands, The

Overlook Press 2001

Target America: Hitler’s Plan to Attack the United States,

James P. Duffy, The Lyons Press 2006

Dresden: Tuesday February 13 1945,

Frederick Taylor, Harper Collins 2004

Six Months To Oblivion, Allan

Ian, Shepperton 1975

Blitz on Britain, Allan Ian,

Shepperton 1977

|