by

Raúl Colon

Rió Piedras

Puerto Rico 00929

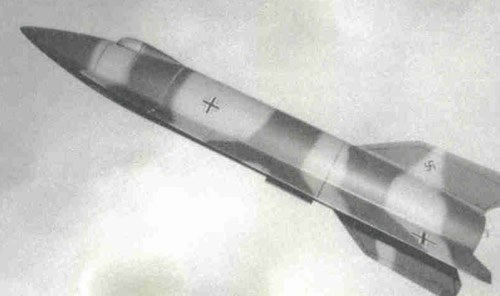

A9

When Adolf Hitler plunged Germany into the

Second Word War he envisioned a short violent contest. Never in his

dreams had he envisioned a prolonged four year struggle, but by 1942 he

was exactly in the middle of his “struggle”. In order to control the

tide of the war, the German leader ordered the design and development of

very advance weapon systems. By this time, many civilian initiated,

dual-purposes projects were underway in Germany. Chief among them were

the V (for Vengeances) weapons platforms. The first of those systems,

the V-1 or “Buzz Bomb” was able to bring terror into the heart of

London. The V-1, which was essentially the first rudimentary cruise

missile, was easy to design and build in large quantities. Next in line

came the famous V-2 rocket. There were several variants of this

impressive missile system.

The more impressive one was the forth

generation variant known simply as the A4 rocket. The A4 was the first

truly military-controlled missile developed system. In short, the A4 was

the world’s first ballistic missile. It was 46’-0” in length with a

diameter of 5’-5”. On the base of the rocket, four fins, with a span of

11’ 8” gave stability to the platform. Prior to fuelling, the A4 weight

in at 8818 lbs. The A4 was able to carry an impressive 1654 lbs warhead.

Fully loaded, the rocket weighed 28440 lbs. The fuel used to power this

massive rocket was a combination of alcohol and liquid oxygen that

consumed itself at a rate of 280 pounds per second. This rate of

consumption gave the A4 only 65 seconds of powered flight. But by the

time its fuel had run out, the A4 was travelling faster than the speed

of sound. Operational range for this rocket was an astonishing 220

miles.

The first A4 was launched on the morning of June 13th 1942 from test

Stand Number 7 at Germany’s main rocket research facility on Peenemunde.

The launch, which was viewed by the Luftwaffe top brass, was successful.

The rocket cleared the launching tower without any problems. If the

lift-off was successful, the flight trajectory was not. After reaching

the dense cloud formation above the Baltic coast, the rocket exploded in

an impressive manner. Nevertheless, the test had proven the feasibility

of the A4’s design. Further tests were made and, on the afternoon of

October 3rd 1942, the A4 made its first successful launch and flight.

The rocket achieved an altitude of nearly 50 miles above Earth and

landed more than 120 miles outside the Test area. After less than ten

tests, the A4 was deemed operational by the Nazis and on September 6th

1944, two of these extraordinary rockets were fired at Paris. Within a

matter of days, A4s were being fired at London and the important Belgian

port city of Antwerp. It is believed that in the later stages of the

war, Germany developed over 5,000 V2-class weapons, firing above 1,000

of them towards the English capital.

As a weapon of terror, the A4 had its use, but it was far too

rudimentary to affect the situation on the strategic battlefield. A new

kind of missile was needed. Range and payload became Germany’s obsession

when it came to its rocket program. Thus the development of Germany’s

next ballistic rocket was centred on those two factors. The new A9

missile was basically a winged version of the current A4 platform.

Engineers at Peenemunde found that once a rocket reached its top

altitude and exhausted its fuel, it would plummet toward the ground

without many in-flight corrections. But, adding wings to a streamline

body will enable the A9 to “glide” to its intended target area. Beside a

flight pattern correction, the installation of wings on the bottoms of

the missile would give the rocket a much better opportunity to explode

above its target instead plummeting hard to the ground as the A4 did.

When a missile hit the ground hard, the subsequent explosion is mostly

absorbed by it. If the missile could glide to its target instead of

plummeting on it, it would hit it more softly causing a bigger explosive

effect. When conceived, the A9 blue prints closely resembled that of the

A4.

It had basically the same frame length and

diameter dimensions. The idea of adding the wings, first proposed by

designer Kurt Patt during the A4 program; was first viewed as too

radical for the A9’s engineers, but as the programme progressed, those

wing structures were viewed as stabilizing and controlling mechanism.

Beside the controlling aspects of the wings, designers estimated that

these structures could actually double the rocket’s operational range.

As promising as the A9 program was, it was not one of Germany’s top

projects until the Allied landings in Normandy. With the Allied armies

in northern Europe, London was now out of the A4 range. Thus on the

summer of 1944, the German High Command ordered the A9 to full

production status despite the fact that the rocket’s new engine system

was not fully tested. Clinging to the faint hope of knocking the British

out of the war, Hitler ordered massive A4 and 9 attacks on London and

its nearby cities and towns. The decision of the Fuehrer basically ended

any hope Germany had of developing a real Inter Continental Ballistic

Missile.

On July 1941, Field Marshall Walther von Brauchitsch, Germany’s Army

Commander in Chief, suggested to Hitler and the Nazi top brass that the

development of a functional and advanced rocket programme would give a

moral boost to the German people. He also, vaguely, mentioned that

Germany should place resources into developing a missile capable of

reaching the United States. It is known that Peenemunde’s secret

Projects Office commenced designing a missile capable of achieving long

distances. The project, which some called the “American Rocket” was

rumored to have began in late 1940. The American Rocket was the

brainchild of Ludwig Roth, a brilliant, yet obscure German designer; who

began looking at the feasibility of installing an A9 missile on top of a

massive booster rocket. The concept, now designated A10, was deemed to

be too technically challenging by most German engineers. The A10 program

was called off soon after. If developed, Roth’s massive rocket would

have had an engine capable of giving it almost 200 pounds of thrust for

around sixty seconds this would had enabled the mounted A9 rocket to

reach an altitude of 35 miles. It was estimated the returning A9 could

have had a range of 2,500 miles in just thirty five minutes.

After the A10 program was terminated, there were discussions of

developing a manned version of the A9 system. Engineers believed that a

manned rocket would have solved the main problem of guiding the rocket

to its target. There were even “talk” that a manned A9 with an A10

booster can actually hit small targets such as the Empire State

Building. The idea was that once the A9 was in clear sight of its

target, the pilot would have bailed out and the rocket would have

self-guided to the intended area. Although the project looked promising

on the drawing board, it never left it. In fact, all work relating to

the A10 booster rocket was terminated in the spring of 1944. Work on the

winged A9 proceeded at much slower peace. The A9 project was cancelled

in the autumn of 1944 because of material and fuel shortages. Although

halted, the A9 and A10 projects did provide Germany with the necessary

data from with which to further develop its operational missile, the A4.

A winged version of the A4 with a new and improved propulsion system,

code named A4b, was developed. Unfortunately for Germany, the Red Army

was closing fast on Peenemunde and all work related to this programme

was hastily suspended in late 1944.

If Nazi Germany would had employed the resources needed to build A10

booster with an A9 rocket, there is little doubt that Hitler would have

had the world’s first true Inter Continental Ballistic Missile. The

extent of German research and development of a true ICBM can better be

explained by Wernher von Braun, the brilliant German scientist who led

the American effort to reach the moon. When interrogated after the war,

von Braun explained that German engineers were commencing the design of

a new booster rocket, code named the A10, which would have been a three

stage, extremely long range ballistic missile. In fact, he described the

A10 as the first moon rocket, meaning that it was intended to get the A9

missile over Earth’s atmosphere. How close Nazi Germany came to actually

develop a workable ICBM is anybody’s guess, but the sheer volume of data

clearly points to a massive German effort to develop such a weapon. One

could suggest that if Hitler and his staff had pressed on with the

rocket program early on in the war the ICBM would have been achieved.

Secrets Weapons of World War II, William B. Breuer, John

Wiley & Sons, New York 2000

The Air War in Europe, Ronald Bailey, Time-Life Books, Chicago 1981

Top Secret Tales of World War II, Patrick Buchanan, John Wiley & Sons,

New York 2000

German Secret Weapons: A Blue Print for Mars, Brian Ford, Ballantine

Books, New York 1969