|

Percival Stanley "Stan" Turner

Percival Stanley "Stan" Turner was born

in Ivybridge, Devon, England on September 3, 1913. His parents emigrated

to Canada when he was a child to Toronto, Ontario. He grew up in Toronto

thoroughly Canadian. Stan enjoyed swimming and earned his Red Cross

certificate to become a life guard. He attended the University of Toronto

studying engineering and flying part-time with No. 110 (Auxiliary)

Squadron as an airman, where he earned his "wings". Prior to the war he

applied to the RAF through the RCAF recruiting depot in Toronto through

the "Direct Entry Scheme". At this time the RAF anticipated a war with

Germany and were actively recruiting from England and the Dominions for

men who could become operational quickly as they would already have pilots

licenses. The RCAF and the government of Canada were slower in

comprehending the danger of Hitler and were not actively recruiting at the

time. He passed the exams and was accepted for a short service commission

in October, 1938. At this time many of the recruits had completed, at

their own expense, initial flight training and had a pilots license. He

and a select group of young Canadian men were shipped to England that same

month for training. He was made an Acting Pilot Officer on Jan. 14, 1939

based on his pilots license and apparent promise as a pilot.

He passed through the initial training

and the Operational Training Unit for fighters and was posted to No. 219

Squadron in October, 1939, exactly one year after being accepted. A month

earlier war had been declared by England and France on Germany following

their invasion of Poland. No. 219 was a night fighter squadron flying out

of Catterick in north-east England. This posting was short lived as the

Canadian government was anxious that a Canadian fighter squadron be formed

in England from one of the new squadrons being formed for the war. The

RCAF couldn't spare any men from Canada so the squadron was to be formed

from Canadians in the RAF, the so-called CAN/RAF pilots. The squadron

formed was thus called No. 242 (Canadian) Squadron, RAF at Church Fenton,

Yorkshire on Oct. 30, 1939. Turner was posted to 242 (Canadian) Squadron

along with most of the pilots that he had travelled with overseas. The

Squadron Leader was S/L Fowler Morgan Gobeil of Ottawa a graduate of RMC,

Kingston, an officer of the RCAF since 1937 and a member of their Siskin

aerobatics team.

Gobeil's first task was to fill out

the Squadron with Pilot Officers from various RAF squadrons and the

Training Pools and push them through to operational efficiency.

November 5 and 6 saw a flood of young pilots arriving at the squadron,

including one who was to rise quickly to fame, William McKnight (at

left). Stan Turner was posted and arrived at Church Fenton on the

20th.

The presence of the Canadian squadron

was revealed to the Canadian public in a press release in December and

suggested that 242 would shortly be a front-line unit, when they did not

have any aircraft, nor had the RAF determined the type they would be

flying. They started operational training with three Miles Master Mk I

trainers, a North American

Harvard trainer and a

Fairey Battle light bomber. They all hoped to fly the hot, new Supermarine Spitfires,

but instead seven Bristol

Blenheim I light bombers showed up in December along with three more

Battles. It appeared that they were to be a light bomber unit. The only

fighters at Church Fenton were

Gloster Gladiator biplanes from another squadron. The Deputy Flight

Commander and the SL started in on familiarization flights, instrument

flying, and twin engine familiarization in the Blenheims.

The Canadian press descended on RAF

Church Fenton to get the "gen" on Canada's fighter squadron. They

generally got everything mixed up, assuming 242 was operational, and

had been in dogfights over France. One published photo showed a pilot

on his Spitfire's wing, (it was the Magister, although with it's Rolls

Royce Kestrel engine it had the vague appearance of a Spitfire).

Mathew Halton queried Stan Turner about the handling characteristics

of the Spitfire, Stan had to side-slip the question as he had never

been in a Spitfire and turned the conversation to other matters. When

not flying, their days were filled with lectures on air force

organisation, aircraft recognition, engines, tactics, signals,

rigging, armament, battle orders and practising in the Link Trainer.

SL Gobeil was also busy pressuring

the RCAF Liaison Officer to have 242 made a day-fighter unit with

Spitfires. He reasoned, with some success, that the making of No. 242

a Blenheim unit would defeat the aim of firing the public imagination

at home. The RCAF took up the quest with the RAF at higher levels. By

mid-December the RAF decided to provide No. 242 with fighters,

although they were

Hawker Hurricanes, not Spitfires, and send them to France in

exchange for one of the currently posted Hurricane squadrons. The

Hurricanes were tougher than Spitfires and could handle the poor

quality forward airfields in France. They were also more numerous so

they formed the fighter squadrons in the field. Also, Churchill was

very leery about sending his best fighters to a forlorn cause for fear

some would be captured and so appraise the Germans of what awaited

them.

On Jan. 5, 1940 SL Gobeil and five

others, including Turner, went to St. Athan, South Wales to take delivery

of the first of their Hurricanes. On the return they ran into bad weather

and had to land where they could. FO Coe crashed on a force-land at

Appleton and was killed. Gobeil nearly came to the same end, overturning

on landing at Culceth. Fortunately, he came out unscathed. The others

reached their waypoint at Ternhill without incident. On the 16th the three

with aircraft tried for Church Fenton, the weather closed in again and

they were forced down all over the midlands. Turner wrote off his aircraft

in a spectacular crash that he was lucky to survive. It turned out to be

the worst winter in over 40 years, with record snowfalls.

Finally, on Feb 10th the weather cleared

enough to ferry more aircraft so that they soon had 12 Hurricanes to start

fighter training on. Air Ministry orders were that No. 242 be operational

for day AND NIGHT! operations by March 12, 1940. Poor weather and night

flying caused their second fatality as PO Niccolls crashed into level

ground at full speed one night. By March 11 everyone in the Squadron

received their shots for overseas service. On March 23 the Squadron passed

their operational exam by the Air Ministry and two days later A Flight

undertook their first operational sorties. Over the next two days the two

flights alternated doing "convoy duties" escorting ships. on April 4th two

officers were posted to France to " recce" locations for 242 in France,

the Adjutant and a senior PO went. They returned two days later. General

movement orders were issued on the 10th with the intent that they were to

move to the continent between the 14th and the 21st of April. But the

Germans ruined their plans, as they did so many others.

The Battle for France

On April 8th the Wehrmacht supported by

the Luftwaffe invaded Denmark and the next day, Norway. The "Phoney War"

was over, the Blitzkrieg war of the Germans had resumed. On May 10th, 1940

the German offensive on France began with simultaneous attacks on Belgium,

Luxembourg, Holland and France. The RAF had six fighter Squadrons on the

Continent, four more were dispatched immediately to support them. On May

13th Fighter Command sent a further 32 pilots as replacements. This move

included orders for No. 242 to go to France. Then they were recinded and

only four officers were ordered to France to fly with other units. FL

Sullivan, and POs Grassick, McKnight and Turner were selected, leaving

that evening. Six more pilots left two days later.

They reported to No. 607 Squadron at

Vitry-en-Artois and were immediately thrust into battle attempting to stem

the tide of Germans flooding into France. Their first combat sorties found

a large group of Henschel

Hs-126 army cooperation aircraft guarded by Messerschmitt Bf-109s. A

fierce battle arose, with the Germans losing ten aircraft and the British

four. One of the four was FL Sullivan, apparently killed in his parachute

by a German fighter.

McKnight and Grassick were posted to No.

615 Squadron while Turner stayed in No. 607. Turner's logbook for this

period was lost, and he didn't seem that assiduous in keeping it up,

anyhow. The British squadrons fought a losing battle in a rapidly

deteriorating situation. The momentum was in favour of the Germans who had

burst through the Ardennes Forest flanking the French defensive Maginot

Line. There was little to stop them as they slaughtered the French tanks

and infantry units being committed piece-meal and the English troops were

forced back to the coast at Dunkirk. Belgium and Holland were quickly

overrun. The rest of the Squadron was ordered to France on the 16th of May

arriving at Lille/Seclin. Ironically, the ground crews were flown to the

continent in a Sabena Airlines Junkers Ju-52 transport. They started

operations in company with No. 85 Squadron.

On May 18th McKnight, Turner and

Grassick were ordered back to England, arriving there the same day in

their Hurricanes. They were granted 7 days leave, although it was

rescinded

quickly, they were quicker and made good their escape. By May 19th the

squadron was forced to fall back further as the Germans advanced. They

were heavily engaged with Bf-109s and Heinkel He-111 bombers

attacking their bases and allied troops. By the 21st they were all ordered

back to England with their Hurricanes. The ground crews were evacuated

from Boulogne arriving in Dover shortly thereafter. They all received

their baptism of fire, knocking down some six enemy aircraft and losing

four of their pilots (one dead, one POW and two wounded).

Finally, the entire Squadron was put

together at Biggin Hill by May 21st. They were now committed to Operation

Dynamo, the extraction of the British Expeditionary Force and French units

from Dunkirk. They flew combat patrols over the coast of France in the

Arras, Albert, Frevent area to prevent German combat aircraft from the

Dunkirk beaches. Their loses mounted rapidly, within two days they lost

one pilot wounded, two killed and one POW. The next day (24th) two more

pilots were killed when they collided over the sea. One Hurricane chewed

the tailplane off the other, then they crumpled together and spun into the

water. Their successes climbed as well, with at least four German aircraft

downed. The 25th saw another loss to the squadron when a pilot

force-landed in England and sustained serious head injuries. Turner

rejoined them on May 25th a bit early from leave, McKnight and Grassick

arrived back on the 26th. By the 27th they had only 12 pilots left, and

Operation Dynamo was now fully underway.

Fighter Command put what resources it

had into supporting the withdrawal from Dunkirk with some 20 Squadrons

covering the ships. However, as in the case of 242 Squadron, hardly any of

them were up to their full complement. The RAF could either fly a lot of

small patrols continuously over the beaches but would not be able to exert

command of the air, or they could fly in a few large patrols during which

time they could dominate the air war. They tried the first, but eventually

settled on the latter. Their task was simple but crucial, to cover the

area between Furnes and Dunkirk, beating off any German aircraft that

might come near the BEF and the Armée de France.

No. 242 Squadron flew uneventful sorties

on the 27th, but were into the thick of the fighting on the 28th. On their

2nd mission of the day five pilots, including Stan Turner, became

separated from the rest in cloud. The section leader spotted a dog-fight

some three miles inland and was heading for it when they were distracted

by twelve Bf-109s, these they attacked instead. Their small formation was

in turn attacked by some sixty 109s. The section leader had fallen out of

control after attacking a German and headed back to England low over the

water. Two others were shot down, one of whom was killed instantly. Turner

engaged a 109 and out manoeuvred it, getting in two bursts from 150

yards. The Messerschmitt went down in flames and PO Turner escaped into

clouds and returned to base. The other pilot was Bill McKnight who shot

down a 109 but claimed that he was in turn hit in the engine, losing his

oil and coolant systems. In his words he reached Manston after "a

determined and sustained chase by the enemy". However, Stan Turner told a

different story after the war. While escaping in the cloud he fired at a

shape that cruised past, which turned out to be McKnight's Hurricane. He

blew off the oil sump and nearly shot down his friend. Back at Manston

MnKnight angrily confronted Turner, then broke down with laughter.

Mistaken identity was common in air battles and McKnight fudged his report

to protect Turner.

On June 8, the entirety of 242 Squadron

was sent back to France, the pilots joined with No. 17 RAF and flew to Le

Mans, southwest of Paris. Two Divisions of English Army remained in France

and more (including the 1st Canadian Div.) were being sent. No. 242 was to

provide air cover for them. Stan recalled that "The battle by then was

so confused, it was often difficult to tell friend from foe." Beside

the runway was a wrecked Hurricane, the result of a fatal crash by the New

Zealand ace "Cobber" Kain while stunting. The CO thought the wreck would

impress on the pilots the stupidity of aerobatic flying. Their stay was

short, they refuelled and took off for Chateaudun NW or Oleans. Their

aircrew flew in on Bristol Bombays and Handley-Page Harrow transports.

Their accommodation at Chateaudun was a set of large bell tents.

On June 9 Turner shot down a pair of

German fighters. His friend Don MacQueen was attacked by two 109s. Turner

tried to get to him in time and radioed for him to bail out, but MacQueen

was shot down in flames and killed. In a cold fury Turner in turn shot

down one of his attackers and then another later on.

Shortly after arriving in France Stan

and his wingman were forced down in a wheat field due to lack of fuel.

They were quickly surrounded by hostile French farmers. There were a few

frantic minutes until they convinced the natives that they were with the

RAF and not the Luftwaffe, although this did not guarantee a warm welcome.

Their duties were to provide air cover

for retreating French army units and to cover the important port of Le

Havre, as it was their evacuation port. On June 13 there was a fire in one

of their bell tents, all of the men escaped from it but their clothing

went up in flames. The German ground advance was threatening their

airfield so they tried to pull back, but all of the airfields behind them

were choked with aircraft. They remained at Chateaudun for the 14th, which

left the ground crews an important few hours to round up some trucks to

move themselves.

It was clear that the Allied fight in

France was rapidly coming to an end, on June 14 the Germans occupied Paris

with a triumphal march down the Champs Elysees. No. 242 Squadron was

ordered back to Nantes and met up with their ground crew.

For their losses of 7 pilots, 2 wounded

and 1 invalided they shot down roughly 30 German aircraft. Turner and

McKnight were leading most of the patrols by now as they were the most

experienced pilots. The ground crews left for St. Nazaire to be shipped

out so now the pilots had to do everything, including arming and re-fuelling

their aircraft. It was a gruelling time with long days and nights spent

under the wings of their Hurricanes to ensure that no one would sabotage

them. Turner recalled:

"One night we went into Nantes, and

soon wished we hadn't. As we came out of a bar, we were sniped at -

probably by another Fifth Columnist. We beat it back to the airfield and

found the canteen tent abandoned. It was loaded with liquor, so we had a

party. Willie McKnight, I remember, refused to drink from a glass.

Whenever he needed a drink, he reached for a bottle, smashed the neck,

and took it straight.

The day France surrendered, French soldiers set up

machine-guns along our runway. "All aircraft are grounded," an officer

told us. "there's to be no more fighting from French soil." We saw red.

A brawl was threatening when I felt a tap on my shoulder. Behind me was

a British army officer, who had come out of the blue. "Go ahead and take

off," he said. "I'll look after these chaps." He pointed to his platoon

which had set up a machine-gun covering the French weapons. The French

officer shrugged and left.

Time was running out. The Germans were over the Loire

River and heading towards us. On June 18 we flew a last patrol over

Brest and made a couple of sorties inland.

Later that day they were ordered to

evacuate. The pilots destroyed several Hurricanes that they couldn't get

started and then smashed the canteen.

"All that booze - it was

heartbreaking. We armed and fuelled our aircraft and climbed in. We were

a wild-looking bunch, unshaven, scruffily dressed, exhausted, grimed

with dirt and smoke. We were also in a pretty Bolshie mood. After weeks

of fighting we were all keyed up. Now that the whole shebang was over,

there was a tremendous let-down feeling. As we headed for England we

felt not so much relief as anger. We wanted to hit something, and there

was nothing to hit. The skies were empty - not a German in sight - and

the ground below looked deserted too. It was all very sunny and

peaceful, and quite unreal. As if the war didn't exist. But we knew the

real war had only just begun."

France sued for peace and Hitler

occupied the northern half of the country and the channel ports, the rest

was governed by the Vichy collaborationist government.

Fighter Command had been mauled in the

Battle of France. It had weeded out the inadequate aircraft, like the

suicidal Boulton-Paul Defiant and the Bristol Blenheim, and showed

deficient tactics, like unescorted bombers, and low-level bombing by

unescorted aircraft. All RAF fighter squadrons, except three in Scotland,

had been in France and had all lost heavily. Many experienced men had

died. The Army had lost all of their armour and artillery and much of

their transport. The First Canadian Division was the best equipped unit in

England. Only 200 inadequate tanks existed to meet the Panzers should they

ever get a toe-hold in England. The situation was grim indeed.

The Battle of Britain

Hugh Halliday in his 242 Squadron

history wrote: "The remnant of No. 242 Squadron was assembled at

Coltishall, near Norwich. They were demoralized, and unkempt, angry at

their ejection from France and what they perceived to be official

indifference. Turner and others characterized their feelings at this time

as "Bolshi" (short for Bolshevic) a term used to indicate rebellion

against Airforce authority. It was time for a change. SL Gobeil was

removed and a new CO arrived. On artificial legs!"

SL Douglas Bader came stumping into

A Flight's hut with his Adjutant. He received a frosty reception from

the Canadians. The pilots were all down at the dispersal huts, on

readiness, when he arrived. At 'A' flight's hut, Bader pushed the door

open and stumped in unheralded. From his lurching walk the Canadians

knew who he was. A dozen pair of eyes surveyed him coolly. No one got

up. Hands stayed in pockets. The room was silent. Watchful.

At last Bader said, "Who's in charge here?" No one answered.

Well, who's the senior?" Again no answer, although men looked at one

another inquiringly.

"Isn't anyone in charge?" A large dark young man said: "I guess not."

Bader eyed them a little longer, anger flaring, turned abruptly and

went out.

In 'B' flight dispersal the eyes again stared silently.

"Who's in charge here?" he asked.

After a while a thick-set young man with wiry hair and

a face chipped out of granite rose slowly and said, "I guess I am." He had

the single ring of a flying officer on his sleeve.

"What's your name?"

"Turner ..." he paused, "sir."

Bader informed Turner and the others that they were a

disgrace to their uniforms and their service and that he intended to knock

them into shape. What did they think of that?

"Horseshit," said Turner. Another pause. "Sir."

With that Bader was on the defensive. He realized that

he had to prove himself to these angry, demoralized airmen. He turned and

stumped out of the hut and over to a Hurricane. The fitter gave him a hand

getting in and he showed No. 242 what he was made of. He showed them a

flawless demonstration of aerobatic flying, despite the fact that he had

never been in a Hurricane. When he slid off the wing he didn't even glance

at the pilots clustered around the flight-hut door. He stumped off to his

car and drove away. The Canadians were impressed.

Later he called the pilots to his office and silently

eyed the rumpled uniforms, the preference for turtle-neck sweaters instead

of shirts and ties, the long hair and general untidy air. At last he

spoke: "You're a scruffy lot. A good squadron looks smart. I don't want to

see flying boots or sweaters in the mess. You will wear shoes and shirts

and ties. Is that clear?"

It was a mistake. Turner said unemotionally, in his

deep, slow Canadian voice: "Most of us don't have any shoes or shirts or

ties except what we're wearing."

"What d'you mean?" Bader said aggressively.

"We lost everything in France." With a trace of

cynicism, Turner explained the chaos of the running fight, how they had

apparently been deserted by authority, shunted about, welcome nowhere,

separated from their ground staff 'til it had been every man for himself,

each pilot servicing his own aircraft, and sleeping under his own wing.

The squadron had suffered nearly 50 percent casualties. When the end had

come they had flown back across the Channel. Since then things had not

greatly improved and they were drifting. There was no self-pity in

Turner's story, only a restrained anger.

"I'm sorry," said Bader. "I apologise for my remarks."

He then loaned them what spare kit he had and personally guaranteed their

purchases in Norwich at uniform shops. Then he talked over their fighter

experience and went flying with each of them. In the mess that evening he

won them over completely with his charm. Finally one pilot put down his

empty pint pot and said, "Hell, sir, we were scared you were going to be

another goddam figurehead".

Within two weeks No. 242 Squadron was a

cohesive unit. They undertook a period of intensive training. They

achieved the highest scores on the RAF air firing range ever posted.

Apparently their Bolshie attitudes were being overcome by Bader, the

upcoming emergency and plain hard work. Bader lived for his squadron and

expected all his men to do likewise. He was everywhere on the base

overseeing all activities. As Turner said to West, the squadron

engineering officer: "Legs or no legs, I've never seen such a goddam

mobile fireball."

RAF 242 Sqdn, 1940. L to R: Crowley-Milling, Tamblyn, Turner,

Saville, Campbell, McKnight, Bader, Ball, Homer, Brown

The muscular Stan Turner was not a mild

man himself, having a large capacity for beer and a penchant for firing

off a revolver in public. The Wing Commander had suggested: "You ought to

get rid of that chap. He's too wild". But Bader saw eye-to-eye with

Turner, a first-class pilot, fearless and decisive.

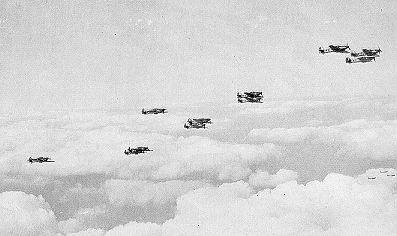

Vics of Hurricanes from RAF 242.

Their aerial tactics remained the

same vics of three aircraft. All who had served in France and survived

understood the versatility of the German finger-four tactics, but

there was no time to re-train even the veteran pilots. Bader loosened

up the vic and used several weavers to watch their tails. This helped

somewhat but the German aerial tactics remained superior until the

English had the winter to revise their manuals and train pilots.

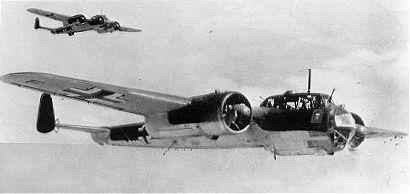

A schwarm of Bf 109Es in finger-four formation.

They were declared operational on July

9, 1940. Their first sorties were to patrol over a convoy. Most historians

have agreed that the Battle of Britain occurred from July 10 to October

31, 1940. The initial period involved skirmishing and the probing of

aerial defences by the Germans. The next few days saw a lot of small

actions as they tested the aerial defences of southern and eastern

England. No. 242 was kept busy for most of July flying cover for convoys

and covering the south-eastern part of England. Sporadic interceptions

showed that No. 242 was not in the main part of the battle.

Denis Crowley-Milling, then a Pilot

Officer with 242 who rose to become Air Marshal, stated "As young and

inexperienced pilots, we were often too excited and fired our guns too

early, from too far away. Fortunately, the armourers put tracer in toward

the end of the ammo load, so that one would come up with a jolt and

realise one didn't have much ammo left. It might have been better for us

if they had put the tracer in first ..." Interspersing tracer was

something that would later become standard practice so the pilot could see

his stream of bullets.

Coltishall, an airfield controlled by

No. 12 Group under Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, was on the

northern flank of the primary battle area, and action was correspondingly

sporadic. However, on August 19th German aircraft raided the field,

killing two men and slightly damaging a building. One of the new pilots

who took off after the bombers spun into the ocean, being killed on

impact. A series of small German missions by three aircraft each kept them

occupied for several days with nothing to show for it.

On August 30 the squadron was ordered to

fly from Coltishall to Duxford, close to London. They did this in the

morning, returning to Coltishall in the early evening. This put them into

the prime battle area at the peak of the battle. That afternoon they were

sent on a scramble to intercept bombers approaching North Weald aerodrome.

Bader led the way west to get the sun behind them. They spotted a large

force of Bf-110 Zerstörers and bombers. Bader charged into the midst of

them, scattering their formation and making them all the more vulnerable

to the Hurricanes. They downed 12 Germans that afternoon, although Turner

did not fly.

From Aug. 31 to Sept 6 they patrolled

over Duxford, Northolt, North Weald and Hornchurch without contacting the

enemy. That is not to say they weren't there, terrific air battles were

being fought, by other Squadrons. So far the Luftwaffe were concentrating

on RAF fields in the south and east of England in areas where they would

have to dominate during the invasion, Operation Seelowe (Sealion). But on

Aug. 24 about 100 Luftwaffe bombers aimed for the Thameshaven oil

refinery. This they missed but hit a residential area causing large fires

and heavy civilian casualties. The English retaliated and bombed Berlin

the next night. Now began a vicious retaliation/counter-retaliation cycle

that Goering felt the Luftwaffe capable of winning. He also thought the

RAF was nearly through, although he was wrong on both counts. The Bf-109

without extra fuel tanks was operating at it's limit over London, they

barely had 10 minutes fighting time at normal throttle before they had to

head back to France. Many didn't make it because they ran out of fuel.

Sept. 7 started like many others had,

No. 242 flew down to Duxford from Coltishall and joined Nos. 19 and 310

flying Spitfires and Hurricanes. With these they made up the "Duxford

Wing". Just before 5 PM they were all scrambled to meet an incoming force

of bombers and fighters. Bader took them up to 15,000 feet and found enemy

aircraft 5,000 feet higher yet. Between 70 and 90 bombers in a tight box

were protected by higher flying Bf-110s and Bf-109s higher yet. They

slammed the throttles through the gates into maximum boost and cut off the

attack. Turner was leading Green section, the last of the Hurricanes to

hit the fray. As he approached the dogfight he saw a Bf-110 shot down in

flames by Bader's section. He then fired at a 110 but before he could

press home the attack he had to avoid a 109. Turner outmanoeuvred this one

and gave it a good burst of machine-gun fire and saw it go into a dive.

Another 109 jumped him, he snapped off a quick burst and took evasive

action. His final score was a single damaged 109, despite the fierceness

of the fight. The rest of the Squadron downed 10 German aircraft for the

loss of one pilot and many damaged Hurricanes from wickedly accurate

defensive fire from the bombers.

Sept. 15 opened with mist but with a

promise of good weather. The Germans sent over a few recce sorties in the

early morning. By 11 AM the British radar plotters had a large force

assembling over France. Only 30 minutes later 100 Do-17 bombers with a

larger number of fighter escorts crossed the Channel.

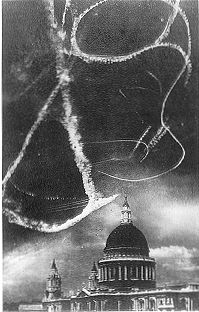

t was to be the peak of the fighting for

the Battle of Britain. The entire Duxford Wing, now

consisting of five fighter squadrons, and four other squadrons were

launched at the massive attack. It was the perfect defensive attack.

The British had the advantage of height, and sun. The three Hurricane

squadrons (242, 302 and 310) were at 23,000 feet in line abreast and

the two Spitfire Squadrons (19 and 611) were stepped up at 26,000

feet. The Germans were at 17,000 with the escorting Bf-109s hovering

close around. This proved to be a faulty tactic that the German bomber

commanders insisted on. The German fighters didn't have room to

manoeuver or to intercept the British fighters before they were

through their protective screen and into the bombers.

It was disastrous for the Luftwaffe.

No. 242 Squadron alone shot down 4 bombers and 2 fighters for only 1

Hurricane lost. Others claimed a further 23 destroyed and 8 probables.

There was a great danger of colliding with another British fighter as

there were so many twisting and firing at the bombers and fighters.

Turner shot down a Do-17. Bader was given the credit for his fine

timing in positioning his squadron and attacking out of the sun.

After a hurried lunch they were

again airborne that day just after 2 PM. Climbing through clouds, AA

bursts ahead showed them that the Germans this time had the height

advantage. The Messerschmitts dove into the British fighters, the

Hurricanes wheeled after them and the Spitfires went after the

Dorniers.

At the start of the battle Turner lined

up a quick shot on a 109 and saw his bullets hit. The German spun out of

control making him think the pilot was dead. But he couldn't watch that

one any longer, a cannon shell exploded near the tail of his Hurricane

throwing him into a spin. He dove through the clouds and pulled up near a

Do-17. He attacked from the side with full deflection. The right-hand

engine started smoking and fell into a gradual dive to explode on the

banks of the Thames. His tail unit was on fire and Stan was seriously

considering bailing out over the Thames Estuary when he flew through a

rain-heavy cloud. To his great relief the cloud extinguished the fire.

Being well out of the battle with a damaged Hurricane and low on

ammunition he returned to base. He received a destroyed and a probable

credit for the day.

On Sept. 16 Turner was jumped from a

Pilot Officer to a Flight Lieutenant and given the job of "B" Flight

Commander. Bader found that the added responsibility curbed Turner's

wildness.

Following further successful battles

with the Luftwaffe a set of medals were awarded to the pilots of 242,

Turner received a Distinguished

Flying Cross (DFC).

Distinguished Flying Cross

- Flight Lieutenant Percival Stanley Turner (October 8th, 1940)

On September 15th, 1940, Flight

Lieutenant Turner succeeded in shooting down one enemy aircraft when his

own aircraft was hit by a cannon shell which put it temporarily out of

control. On recovery he saw and attacked a further enemy aircraft, which

he destroyed, afterwards bringing his own damaged aircraft safely back

to its base. This officer has personally destroyed a total of ten

hostile aircraft during engagements over Dunkirk and England. He has

proved himself a most courageous and capable leader, displaying coolness

and initiative in the face of the enemy.

Sept 27th was the last of their

participation in the heavy fighting of the Battle of Britain. They were

back to patrolling from Coltishall and Duxford but few enemy aircraft

showed themselves. They returned to Coltishall at the end of November and

to Martlesham Heath for December.

The Luftwaffe had exhausted itself in

the Battle of Britain, so that the RAF went on the offensive in early

1941. They began a series of offensive missions against German air units,

aerodromes and military installations in Occupied France, Belgium and

Holland. These missions were code named "Circuses" and were flown by a few

bombers with massive fighter support. Turner and 11 others flew with the

first Circus to Guines aerodrome near Calais. Their duty along with

another squadron was to provide forward support by shooting up St.

Inglevert airfield to tie down the 109 fighters. Two days later they

continued with a "Mosquito" mission, later named "Rhubarbs" for their

low-level flight plan. SL Bader and FL Turner conducted the first as an

armed pair of low flying (600 feet max.) fighters. Half way across the

Channel they spotted a pair of

German Schnell or "E" boats and a converted fishing boat. They turned

in towards them and, in loose formation, attacked. Bader described it in

his report:

"Both opened fire together at a

height of 50 feet and speed 200 mph. Saw bullets strike water ahead of

"E" boat and then hitting "E" boat. Got one burst from front guns of "E"

boat - no damage. F/Lt. Turner having converged slightly on me, turned

away to avoid slip stream as we passed over "E" boat. One burst from

drifter before I opened fire and none as my bullets struck drifter.

Passed over drifter and made for home with F/Lt Turner in formation. Did

not stop to observe damage to boats but "E" boat must have had a lot as

we could see bullets from 16 guns hitting the boat; drifter probably did

not receive much damage - probably killed a few of the crew."

The pilots were exhilarated at this new

low-level attack mission, but they were lucky and had likely surprised the

E-boats. Low level attacks turned out to be extremely deadly. The same

day as Bader and Turner's mission FO Willie McKnight and another pilot

attacked ground targets along the coast. McKnight, the squadron's leading

ace, died in the attack, likely hit by anti-aircraft ground fire. Also

that same day FO Latta was killed in another low-level attack of dubious

value to the war effort. In one day the Squadron lost some of their most

experienced pilots in return for little damage to the Germans. This was to

be the pattern for Rhubarbs, with some other notable losses in the RAF,

such as fighter ace WC Stanford Tuck.

On Feb. 8 Turner, leading two others,

was scrambled to intercept an approaching aircraft. Despite cloud and haze

they intercepted an all black Do-17 bomber. Avoiding the defensive fire

Turner lit into it destroying the right wing and fuselage, setting one

engine smoking. It escaped into the cloud and one wingman went after it.

He was heard over RT that he was landing in the sea, so Turner quit

hunting the Dornier and went to look for his wingman. He never found him.

No one did. His body was never recovered. On Feb. 15 Turner damaged a

Ju-88 over the North Sea, and intercepted a 109 in the afternoon but lost

it in cloud. At the end of February, they received a new aircraft, sort

of. It wasn't Spitfires, but the 12-gun Hurricane IIa. March 18 saw SL

Douglas Bader promoted to Wing Commander of the Tangmere Wing (145, 610

and 616 Squadrons), in his place came SL Treacy.

April was a disastrous month for No. 242

with the loss of six pilots, including FL Tamblyn, one of the few original

pilots left. Three pilots, including SL Treacy died in a single mid-air

collision. Bader had problems of his own, he had to rest the SL of 145

Squadron and asked the AOC, AVM Trafford Leigh-Mallory, for Turner.

"By all means," replied Leigh-Mallory. "I'm glad you

asked for Turner because he is getting to be a bit of a nuisance in

objecting to flying with anyone else."

The AOC no doubt was recalling Stan's

reactin about a month before when he had promoted Bader to W/C Flying.

Stan was present and, with his pipe stem jabbed right into Leigh-Mallory's

chest, saild "look here, Sir, you can't go and post our CO away because we

won't work for anyone else." No doubt the AOC was peleased to get Turner

out of his way. On the 13th FL Turner was promoted to Squadron Leader and

sent to command No. 145 Squadron.

145 Squadron

No. 145 Squadron was still flying the

Spitfire II on sweeps over France and Turner made a quick transition from

the Hurricane to the Spitfire in a day. The next day he lead 145 Sq. in a

historical sweep over France called Circus No. 1 - the first large-scale

operation over France by Fighter Command. A veritable horde of Spitfires

(36 from Tangmere, 36 from Biggin Hill and others for target support and

rear cover) escorted a group of Blenheims to raid Cherbourg. The Luftwaffe

declined to rise to the bait.

As the Germans had made several

successful raids on Tangmere, Bader spread his squadrons out, 145 was

posted to nearby Merston at night and flew from Tangmere in the day. The

other innovation was the implementation of the finger four technique,

identical to what the Germans were using at the time. It was also during

this period that Turner developed his style of leading men in action. He

demanded instant attention to his orders and promptly got rid of men who

did not do as he instructed. Finally, in June, on a sweep of the Le

Touquet area the Germans came up to do battle, the first sign that the

Luftwaffe were still in operation. But the German high command surprised

everyone with Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia.

On June 25 they flew two Circuses, the

second netted Turner a destroyed. Over Westhampnett he spotted some 109s

about to attack the other squadrons and drove them off. More Bf-109s

appeared and he led his squadron on another dive this time with more solid

results. At 300 yards he fired a large deflection volley that hit his

target square in the fuselage, streaming white and black smoke the German

plunged to the ground. However, a fighter pilot who stays fixated on his

victim, soon becomes one himself, so Turner did not follow the final dive

of his opponent. He claimed a probably destroyed.

In early July they finally received a

much needed update in equipment, the Spitfire Va, with which to

effectively combat the new Messerschmitt Bf-109F. It came with a more

powerful engine and in place of six 0.303 machine guns it packed four

0.303 mgs and a pair of 20 mm cannons. In late July he downed a 109 in his

old stomping ground east of Dunkirk, although it was nearly the death of

him. They were loitering at 3 - 4,000 feet waiting for bombers to escort

when they were bounced by 8 Bf-109s. They turned to evade them and

repositioned themselves behind the fleeing Germans. They, however, made

the mistake of turning back towards the Spitfires without climbing first.

This gave Turner a shot at one that apparently did no damage, his wingman

chased another down low over the Channel, leaving Turner alone. Four 109s

kept him busy exchanging shots but none hit him as he twisted and turned

away from them. Another 7 109s joined the fray and made everything a

confused mess as Turner used their numbers against them. They generally

got in each other's way. Finally seeing a chance he dove out of the fight

to England. His wingman had made it made after killing his quarry and

reported that Stan's first shots must have killed the 109 pilot as he had

dove straight into the Channel. This raised his total to 10 1/3 destroyed

(3 unconfirmed), 1 probable, 4 damaged.

Johnnie Johnson, Britain's No. 1 ace,

was at that time a pilot in 616 Sq. He recalled Turner:

"Fearless and a great leader. He was given the most

difficult job of all - that of top cover to ourselves and No. 610

Squadron. Teh Messerschmitt 109F possessed a higher ceiling than our

Spitfire IIs, so that they still swarmed above our formations; and

Stan's task was to hold his squadron together in their high sundown

position and ward off the highest 109s. He was always there with his

boys; always fanning across the skyin the right position; and always

ready to chortle some ribald comment over the radio ... The Wing was far

weaker after Turner's departure, for during the last few weeks we had

fought hard together, and it would take a long time to work up the new

squadron".

He led this squadron in this area on

sweeps until October, 1941, receiving a bar to his DFC in August.

The Citation read:

This officer had led his squadron on all sweeps over

France, and has set a splendid example by his quiet coolness in the face

of the enemy. he has been resposible for the destruction of at least 12

enemy aircraft."

Turner tried like a fury to prevent his

posting out of 145 Squadron, and from posting the squadron on easier

duties, but to no avail. He was given a two month rest by being posted as

the Staff Operations Officer to 82 Group HQ in Northern Ireland until

Dec., 1941. This also got him acquainted with the command structure and

staff.

411 Squadron

He was next given command of No. 411

RCAF (Grizzly) Squadron, although he remained in the RAF (they called such

men CAN/RAF pilots). Discipline in 411 was poor and losses were mounting.

Stan applied his furious energy and command to pull them together. They

continued the same sweeps, and bomber escorts over France and the low

countries. When in February he was posted out the Squadron diary read:

Information received that S/L Turner, DFC & Bar, is to be posted Overseas

shortly." A rush of applications followed for the same posting, all but

that of P/O McNair were turned down. Stan was heading to the most active

air front in the war, Malta. Stan was a fast learner, and had developed a

reputation for being able to impart the new concepts of flying the 'finger

four' formation to other pilots in a minimum of time, and was capable of

pulling a bunch of trained men together into an efficient fighting team, a

Fighter Squadron. In Feb. 1942, he was given command of 249 Squadron on

Malta.

Malta

He was not only to command 249 Squadron,

he was also tasked with revitalizing the entire fighter operations on

Malta by getting all of the squadrons up to speed on the new tactics just

prior to them converting from Hurricane IICs to Spitfire Vs. Laddie Lucas

in his book "Malta, The Thorn in Rommel's Side" tells the story of

Turner's time on Malta very well.

Prior to leaving for Malta Turner met

and inspected several of his new officers. Lucas relates:

The Canadian squadron leader, whom I did not know,

but to whom I would later owe so much, stepped forward as I came

perfunctorily to attention. His first action was to flick apart my

unbuttoned service greatcoat, which I had not yet removed. A cursory

glance inside confirmed the absence of any decoration underneath the

wings on my tunic. A look of deprecating disdain showed at once on his

face. A flight lieutenant without a gong was hardly worth a damn.

Our first impression of Stan Turner was distinctly

unpromising. Apparently unforthcoming and uncommunicative, he took no

trouble to hide his belief that anyone who came from 10 Group of Fighter

Command was largely beyond the pale, by comparison with his adherents

from 11 Group in southeast England.

Turner had already become something of a legend,

although I did not know it. Maybe this was one reason for the stiff

reception.

Now this rugged and curiously diffident exponent was

being sent out to Malta to sharpen up the Island's flying, what little

there was of it considering its paucity of serviceable aeroplanes. For

an officer who had already had a basinful - and showed it - it was quite

an undertaking. What Turner was able to accomplish in his first month in

the Mediterranean deserves a place in the history books. His was an

unforgettable contribution of which, at this first meeting, he gave not

the slightest hint.

Two days earlier the German Navy and Luftwaffe had

managed to get the pocket battleships Scharnhorst and

Gneisenau and heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen past England via the

Channel and into German waters. This extraordinary escapade had the

effect of projecting our leader's acute operational mind, which was by

now super-allergic even to the mention of the Luftwaffe's fighter

aircraft, well forward to the affairs of the next day. Having told us

that we would be leaving early by Sunderland flying boat for Gibraltar,

en route for Malta, he added a cautionary rider.

"You guys may as well know that we'll be skirting

Brest in broad daylight as we head down south for the Bay of Biscay and

Gib. But if it helps any, remember that, for this party with the ships,

the Hun will have moved all of the 109s and 190s from the Brest

peninsula up to the Pas de Calais to fly the cover through the Straits.

It's unlikely that they will have returned so soon. Breakfast will be at

0530."

As he mentioned the 109s and the 190s, I noticed that

Stan, out of habit, swivelled his head round and was searching the

ceiling for imaginary aircraft from 5 o'clock to 7 o'clock, 5000 feet

above.

Next morning the weather was poor, blowing strongly

and making it questionable for a takeoff in a flying boat. To the flying

boat commander he stated "You're the captain of this aeroplane and it's

up to you and your flying control masters - no one else - to make the

decision. But if it's marginal, then let's get the hell out". It was a

characteristic stance. They got off with their fair share of bruises

from smacking into the waves during takeoff.

It was a curious fact of war that for a fighter

pilot, accustomed to being alone in a small cockpit, doing everything

busily for himself in the air, the role of passenger in a great hulk of

an aircraft, with nothing whatever to do save sit, wait and listen, did

not come easily. With Turner, the unease was manifested by a continuous

vigil at one of the portholes on the port (enemy coast) side of the

Sunderland. What good it would have done him - or anyone else - had he

happened to see with his acute eyes a single or twin-engined fighter was

not explained. But it clearly tempered his up-tight nervous system to be

vigilant.

His behaviour showed to the observant that after the

trials of France, Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain and the sweeps over

enemy-occupied territory, all of which covered the best part of two

pretty hectic operational years, Stan's nerve-ends were raw and exposed.

It was a little difficult to understand what the forthcoming Malta

experience was going to do for this condition save exacerbate it. After

all the fighting, Stan was strung up so tight you almost felt you could

'ping' him.

Two days later, as the Sunderland flying boat touched

gently down on the waters of Kalafrana Bay at the start of a perfect

spring day, evidence of the deficiency of the Hurricane was provided

almost at once. After twenty-one hours in the air from England, it

wasn't a sight to gladden a tentative heart.

As the tender took us from the aircraft to the

quayside, and we began to make our way to the nearby Mess for what would

purport to be breakfast, the sirens began wailing out their warning of

the Germans' first air raid of the day. Turner, who was in the van of

the party, quickened his step and started scanning the brightening sky.

Within moments, the sound of fighter aircraft, climbing at full bore,

heralded a scene which was to issue ominous notice of events to come.

A strung-out, antiquated VIC of five Hurricanes,

breathlessly clambering to gain height, was heading south-east out of

the early morning haze in a palpably forlorn quest to achieve some sort

of position from which to strike at the incoming raid.

High above, three sections of four Me-109s in open

line-abreast formation were racing at will across the powdered sky, the

'blue note' of their slow-revving Daimler-Benz engines spelling out a

message of unmistakable supremacy.

Stan Turner, empty pipe turned upside down in his

mouth, gazed up, astonished, as the Hurricanes were soon lost in the

haze. Stunned by what he had seen, he removed the pipe from between his

teeth. "Good God!" he muttered, and hurried on to the Mess.

The impact of the scene we were now confronted with

in Malta was overwhelming. But it wasn't just the endless bark of

gunfire, the scream of bombs or the extensive rubble which had once been

sand-coloured stone buildings that made for us, the impact. It wasn't

only the lack of fuel and transport and, with it, the immobility ... It

wasn't solely the monotony of the food and the predictable diet of

McConachie's stew or bully beef, local 'gharry grease' for margarine,

hard biscuits, bitter 'half-caste' bread or the paucity of it all; nor

was it the surprise at seeing the spare look of squadron pilots and the

pinched, drawn faces of those who had been sweating it out on the Island

for weeks and months, without rest or respite, in unequal combat with a

superior enemy; nor, again had it al to do with the diminishing aircraft

strength and the absence of spare parts with which to maintain

serviceability.

It was something much more comprehensive. It was the

primitiveness of everything and the governing lack of essentials in

Malta by comparison with the well-endowed, orderly stations we had left

behind so recently in Fighter Command, with their profusion of stores,

supplies, equipment of all kinds and even aeroplanes. We realized that

here, on this battered and isolated Island set in a mainly hostile sea,

everything had to be improvised. The do-it-yourself, make-do-and-mend,

cobble-the-parts-of-three-damaged-aircraft-together-to-make-one-fly

concept ruled everywhere. This was what overwhelmed us, and the

remoteness of the place - 1000 miles or so from Gibraltar in the west

and some 800 or 900 from Alexandria in the east, with the enemy

controlling much of the coastline to the north and to the south.

"Goddam this," said Turner dismissively, as he

clambered into a front seat beside me on the bus. It wasn't exactly

clear to what or at whom his brief comment was directed. I assumed that

is was intended to be all-embracing.

The modern concept had not yet percolated the old

Hurricane squadrons in Malta and this is where Percival Stanley Turner,

who had flown the line abreast, finger-four principle with such signal

success with the Tangmere Wing, made his mark on the Island and at

Takali in particular. In the introduction of his instant change of

tactics I was a learner, a first-hand witness, an accomplice and an

accessory after the fact. What Turner was to achieve against some

initial, outmoded and deep-seated opposition in his first five or six

weeks in Malta, during the critical transition from Hurricanes to

Spitfires, deserves a place in the history of the Mediterranean war. It

stamped the Canadian with Lloyd, the AOC, and the recently installed

Group Captain A.B. Woodhall, who quickly became the Service's

outstanding controller of the war, as a principal architect of victory

in this gruelling contest. From an operational standpoint, the

circumstances which Stan Turner and his other newly arrived cohorts

found at Takali were lamentable and catastrophic. Out of some sixty or

seventy aircraft in varying states of damage and disrepair, there was a

daily average of a dozen serviceable Hurricane IIs on the Island against

Kesselring's front-line strength of some 400 aircraft in Sicily.

There was also a heavy, oversupply of pilots, as

there were so few aircraft. This meant that their fighting form was

blunted. Fighter pilots require frequent flying to maintain their

abilities, not to do so dulls the edge so that after a while they are

more of a hindrance in the air. Turner, with Woodhall's support, began

by creating a pool of serviceable aircraft and making it available, in

turn, for nominated squadrons to draw on. Not only did this give a

squadron commander a chance to put up one, two or even three sections

of four aircraft; it also offered the opportunity for Stan to look at,

assess and, where necessary, revitalize the operational characteristics

of individual units. Even with this scanty force, a semblance of purpose

and method began to be injected into this tenuous exercise.

One morning - it was 24 February - Turner took me by

the arm in the Mess at Mdina and led me out onto the balcony overlooking

the airfield. Although no one was about he followed his usual ritual of

looking round to ensure that he would not be overheard.

"Look here," he said, "you'll be one of the flight

commanders in the Squadron and I shall look to you to help me with

changing the flying pattern here. We can't have any more of this goddam

VIC formations otherwise we'll all get bumped, that's for sure. I want

you to learn this line-abreast stuff with me. And quickly." He then

removed the empty pipe from his mouth and with it started marking out on

the dusty floor of the veranda all the line-abreast manoeuvres,

emphasizing the need to get the cross-overs in the turns, as he put it,

"spot on". "This way," he said, " a couple of guys will never get

bounced: attacked maybe, yes; but never surprised, no kidding."

Reflective, yet impatient, he looked down at the

airfield. "They've got several serviceable aeroplanes down there this

morning. If Ops have got nothing on the table we'll grab a couple of

aircraft and run the sequences through. If a raid develops while we're

up, we'll get stuck into it."

My log book shows that we were airborne for

thirty-five minutes in our clapped-out Hurricane IIs. My recollection is

that during that time it seemed that Stan had the throttle of his

aircraft permanently 'through the gate'. It was all I could do to keep

station. His taut nerves dictated his air speed. All the while, Woodhall,

controlling from the 'hole' in Valletta, was in touch over the R/T, his

deep, unhurried voice dispensing confidence.

'Stan,' he said, rejecting the Squadron's 'Tiger'

call sign, 'there are some little jobs at angels 20 going south very

fast. They may be working round up-sun behind you. Keep a good look

out.'

'OK, Woody,' said Stan, 'I can see them.' With that,

he seemed to find a bit of extra boost and headed up towards the sun.

"we'll just have a swing round,' he said, over the R/T, 'and see if we

can get at the bastards.' There wasn't a chance of it.

Nothing doing, we went back to Takali and landed

having done few of the manoeuvres Stan had been talking about. We walked

back to what had once been 249's dispersal hut from our aircraft in

their sandbagged pens. The CO lit his pipe. "That's it then," he said,

"all there is to it. Just remember to keep the speed up. It's no good

floating about round here."

I had seen nothing, and broadly speaking, done

nothing save fly a vibrating Hurricane flat out for half an hour, yet

for some inexplicable reason I felt I had moved up into Division I of

the Flying League. When he wanted to - and only when he wanted to - Stan

Turner had the capacity for making a follower stand taller than he was.

No kidding.

In his second sortie against the Germans

attacking Malta he, and his wingman, were shot down in what he described

as a "comedy of errors". Eight of them had sortied to defend Malta, they

split up to more easily find the Germans. Turner and his wingman spotted

them first.

"I and one of my pilots set off to intercept four

109's coming in over Gozo. I saw them high above me, then lost them in

the sun. Ground Control said they would steer us ... some minutes later,

I realized something was wrong and suspected that Control was plotting

us as the 109s ... a new vector from Control immediately following this

thought, confirmed that suspicion and I gave the order to break. The

turn had just started when the cockpit exploded in a mass of oil, glycol

smoke and fire. The 109s had arrived and must have considered me a

goner, because they did not follow me down to make sure. I managed to

get the machine under control just prior to crashing near Luqa ... I

awoke in hospital. My No. 2 did not return."

No. 249 Squadron had to fly those

clapped-out Hurricanes for another month against the Messerschmitts. But

it taught the new guys what the old hands had been going through for the

past three months. Those people who flew with Stan Turner in that month on

interceptions learned a great deal about flying and fighting in the line

abreast formation, essentially identical to the German's finger four.

Turner's experience and all-round ability wasn't apparent until you

witnessed it first hand.

After two weeks on the island Turner

gave the AOC (Sir Hugh Lloyd) and GC Woodhall his blunt and frank

appraisal of the conditions regarding fighter aircraft on Malta. 'Either

sir,' he said to Lloyd, 'we get the Spitfires here within days, not weeks,

or we're done. That's it.' There was no mistaking his purpose. Turner's

ultimatum came at the same time as a signal from the Chiefs of Staff in

London to the Commanders-in-Chief in Cairo.

Our view is that Malta is of such

importance both as an air staging post and as an impediment to enemy

reinforcement route that the most drastic steps are justifiable to

sustain it. Even if Axis maintain their present scale of attack on

Malta, thus reducing value, it will continue to be of great importance

to war as a whole by containing important enemy forces during critical

months.

In this time period, to highlight the

importance of Spitfires to the defence of Malta, 229 Squadron equipped

with yet more Hurricane IIs, was transferred from Gambut in North Africa

to Malta. Within a month the squadron was declared non-operational. Of

it's 24 aircraft nine were shot down, and seven damaged reducing

operational strength to 8. Of it's pilots four were killed and five

wounded. All of this for no claims of enemy aircraft destroyed.

Malta was now in desperate straits, the

February convoy from Alexandria had failed to reach the island due to

intense bombardment from Ju-87 Stukas and Ju-88s flying from Crete. The

inhabitants were facing acute shortages of everything, to the point of

starvation, including pilots. 'Operation Spotter' was planned to deliver

Spitfires using the aircraft carriers HMS Eagle and HMS Argus.

However, the elevators on Argus were too small to fit Spitfires, so that

left only Eagle capable of delivering modern fighters to Malta. It would

have to steam to within 650 miles of Malta to fly off the fighters. The

Spitfires would have to take off in only 667 feet (the length of Eagle's

deck) with a 90-gallon belly tank. They would take off with flaps deployed

to the half way using wedges as Spitfires had only two flap positions,

full up or down. Once in the air the pilots fully deployed the flaps, the

wedges would fall out and then they would raise the flaps. The fate of

Malta depended on these fighters, for only Spitfires flying at the extreme

of their range could protect a convoy in the extremely dangerous "Bomb

Alley" area of the Mediterranean south of Crete.

Turner summed it up for his squadron,

"You guys may as well face it. The chips are down on the table. This

goddam operation had just got to succeed. If it doesn't, God help us, no

kidding."

The first attempted fly-off from the

Eagle on Feb. 28 was a fiasco. The initial fault with the aircraft was an

air lock in the supply pipe from the belly tank, preventing it's use,

thereby making it impossible for the Spitfires to reach Malta. The entire

delivery force returned to Gibraltar. None of the belly tanks had been

tested prior to leaving England. Then the armourers inspected the

Spitfire's four 20 mm cannons (they were Spitfire Vcs). They found that

they needed to be properly set-up as none of them had been test fired in

England. After this, the riggers discovered that they had no spare parts

for the aircraft. One of the highly valuable fighters had to be scavenged

for parts. By the time Operation Spotter was back on in mid-March the Axis

were well aware of it. The Eagle and the rest of the fleet were shadowed

for 9 hours just prior to the dispatch point. All fifteen Spitfires and an

escorting force of seven Blenheim 'fighters' reached the island safely.

Due to scheduling delays the further 16 Spitfires were delivered in two

batches of nine and seven by Eagle on March 21 and 29, 1942.

Stan Turner was quick in exerting his

influence to acquire the new aircraft for 249 Squadron. 'If it's the last

goddam thing that I do, I'm going to see that 249 is re-equipped with

these airplanes first'. Stan was true to his word, but the small number

delivered robbed the RAF of a critical mass of fighters to effectively

combat the ME-109Fs.

The Luftwaffe's response was quick

and decisive. General Bruno Lörzer stepped up the weight of bombing

missions to Takali Field and the number of fighters escorting the

bombers. Making the addition of a few Spitfires a drop in the bucket

compared to the fighters against them.

By the end of March Stan Turner was

utterly spent as a Squadron Leader. He had survived nearly two years of

continuous battle and had learned much of value to the RAF and would

return much to the service. He was promoted to Wing Commander Flying,

which on Malta was largely a ceremonial posting, and went to work for AOC

Lloyd. His operational time on Malta was up.

April on Malta was sheer hell for all

involved, with the Luftwaffe dropping over 7,000 tons of bombs on it.

Spitfires continued to be delivered in small batches but they were quickly

used up, either destroyed in bombing raids or overwhelmed in the air. By

the end of April the senior RAF officers on Malta, AOC Hugh Lloyd, GC

Woodhall and WC Turner were all exhausted. Lloyd was replaced with the New

Zealander AVM Keith Park who had run 11 Group during

the Battle of Britain. Woodhall and Turner had both been in 12 Group and

as such were firm supporters of strategies espoused by AVM Leigh-Mallory,

which Park had vehemently disagreed with. It wasn't likely that Park would

put up with Turner for long. As it turned out, in slightly less than two

weeks Park, in Turner's words "had him off the Island".

He returned to Gibraltar where he

organized a more effective resupply of Malta with Spitfires. Operation

"Bowery" involved the use of the USS Wasp and HMS Eagle.

Prime Minister Churchill had made an arrangement with President Roosevelt

to use theie larger carrier to carry Spitfires along with HMS Eagle.

The Wasp could carry 50 to Eagle's 17, in any event only 46 were on board.

In an effort to conceal the operation the AOC Malta (ACM Keith Park) had

only 12 hours notice of the landing time. RAF Squadrons 601 (County of

London) and 603 (City of Edinborough) were chosen to fly the 46 aircraft

to Malta.

Within an hour of landing the radar

plotters showed the Luftwaffe were up and leaving their bases in Sicily.

It took three hours to get all of the Spitfires refuelled, and rearmed due

to the excessive security. Also, despite assurances that the cannons had

been air-tested in England and were set-up, there was a problem with

faulty ammunition. All of the regular hands took off in what new Spits

were ready and were into the first of a series of heavy raids intended to

destroy as many of the new fighters on the ground as possible. The Germans

were quite successful. Forty-eight hours later only seven of the forty-six

Spitfires remained fit to fly. The old hands could only look at each

other. It was Malta's darkest hour.

Turner returned to the Maltese

air-control centre and took on an extra, most unappealing, duty. He

organized and led ad hoc sections of Hurricane IIC fighter-bombers

and operated at night over Sicily, raiding the German airports. It must

have been Keith Park's way of rewarding him. There was no mention of how

successful these operations were, for a Hurricane could carry only two 250

lb bombs and were not designed to either fly at night or dive-bomb.

In August he secured a posting to HQ

Middle East in Heliopolis, Egypt as the Senior Controller, Sector

Operations Room, a skill he had picked up from GC Woodhall while on Malta.

He made the transfer at the reduced rank of Squadron Leader because the

rank of Wing Commander Flying from Malta was not recognised by RAF Command

as a genuine rank. He didn't get along well with his senior officer and

was sent to Alexandria as a tactical observer and adviser to the Royal

Navy. One of his duties as a controller was to join the cruiser HMS

Coventry to coordinate air and sea attacks in an ill-fated venture

against Tobruk on Sept. 10, 1942. Again, he nearly lost his life, as the

Coventry was sunk more than a mile from shore. His log book described this

operation:

"September 10. Joined HMS Coventry to act as

Observer for a combined operation against Tobruk. Coventry and 12

destroyers sailed from Port Said on Sept. 16. Shadowed from dawn - HMS

Zulu and Sikh left main party to go inshore - delay in getting troops

away after air bombardment. Stop resulted in enemy spotting Zulu and

Sikh - HMS Sikh pounded by shore guns and destroyed despite Zulu's

attempts to assist. Zulu attacked by bombs next day. Coventry going to

assistance of Zulu was attacked and put out of action by 15 plus

bombers. Had to be destroyed by torpedo. Myself and survivors picked up

by HMS Dolverton. Whole action from beginning doomed to failure - too

ambitious."

Following this he joined the Royal Navy

on Operations Portoullis, Stone Age, Pocket and Burner, mostly escorting

convoys to Malta in November and December. He flew a bit while with HQ in

North Africa with 889 Squadron of the Fleet Air Arm teaching them the

basics of air-to-air combat. He was 29.

Finally, on Jan. 23, 1943 he was ordered

to reform 134 Squadron RAF then at Shandur near the Suez Canal. They were

flying Hurricane IIbs. They were to move up to an active zone of the

Middle East theatre and develop an especially low level method of ground

attack using an early form of napalm. The tactic was for low-level attacks

against tanks and hardened vehicles dropping fire bombs on them that

would, in a gruesome manner, destroy the vehicle and men.

Turner with No. 134 Squadron

In his old style Stan demanded every

drop of sweat from his pilots. He had been chosen because of his great

work on Malta getting the squadrons there up to speed and organised. He

set the example for 134 Squadron himself on low flying. There were many

clapped-out tanks and trucks to use as targets in the desert, and Turner

pressed in too close to one of these, caroming off a turret, while hitting

the tank with a dummy bomb. He took off one and a half propeller blades

and tried, unsuccessfully to chug back to base. He pranged it into the

sand 20 miles short. Fortunately, he was not hurt and was picked up by a

British patrol two hours later. He served with the squadron from January

to June, 1943. Five of the squadron were sent up to the front but they

were never used as the North African campaign drew to a close. It was just

as well, low-level Hurricanes were quite vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire.

Many anti-tank Hurricane pilots were lost on operations using 40mm cannons

under the wings of their aircraft.

417 RCAF Squadron

In April, 1943, No. 417 RCAF Squadron

moved up from the Nile Delta to begin operations as part of 244 Wing in

Tunisia. On the second day of operations their inexperience showed when

they were bounced by 20 Bf-109fs with the loss of four aircraft. In May,

the desert fighting ground to a halt as the Afrika Korps was rounded up

and the remainder of the Luftwaffe made its way back to Italy. They

settled in and began to prepare for the invasion of Sicily, "Operation

Husky". In an attempt to rebuild the inexperienced and demoralized

squadron, HQ posted into 417 a pair of experienced Flight Lieutenants,

Patterson and Houle, and was looking for an experienced Canadian Squadron

Leader who could rebuild 417 and take them into potentially heavy fighting

in Italy. AVM Broadhurst felt that "owing to the lack of operational

experience of the Squadron as a whole, that strong leadership and an

officer of outstanding operational experience should be posted" to No.

417. Other than not being in the RCAF, he was CAN/RAF, SL Stan Turner was

perfect for the job. With at least ten enemy aircraft destroyed and four

or more 'probables', two DFCs, and more than seven hundred hours of combat

flying to his credit, he had a reputation as a disciplinarian where

business was concerned, 'deadly serious' in the air but 'one of the boys'

in the mess, and he was a Canadian, who understood and appreciated the

foibles of his fellow countrymen, whatever badges he might wear. In June

Turner was posted to 417 as the CO. Group Captain (then Flight Leader)

Hedley Everard wrote extensively of his time with the squadron in his

biography "A Mouse in My Pocket".

Turner with G/C Kingcombe and G/C Campbell, Dec.

1943

"The Squadron's arrival in Malta coincided with the

arrival of a new commanding officer and his deputy. Both were veteran

leaders from RAF units. The new squadron leader (SL Stan Turner) wore

battle honours earned during the Fall of France and the now famous

Battle of Britain. He was both fearfully and affectionately called "The

Bull".

The Bull was a slightly-built,

city-bred Canadian with tight, curly, red hair above watery blue

eyes. Immediate compliance to his orders was now essential for

survival in his Unit. Many of 417's mouthy pilots found themselves

airborne to Cairo on a transport the same day. His deputy (FL Albert

'Bert' Houle, right) was also completely intolerant of breaches of

air discipline.

Within two days, challenging air

drills, lead by 'the Bull and Bert' had eliminated all the 'bad

apples'. Replacement pilots were treated less harshly and coached in

the ability of the pilots of twelve Spitfires to act as a team in

battle tactics. Individual tail-chases were practiced. Basically

these were dog-fights between two Spitfires where the aim of the

target aircraft was to lose his "tail" by any manoeuvre or

combination of tricks. All guns were made safe before flight and

only the camera gun operated, so results could be accurately

analysed.

In those last days of June we made a number of fighter sweeps over enemy

territory, but few Axis fighters rose to the challenge of two dozen

Spitfires. Limited engagements did occur but without positive results.

It was taboo to break formation and chase decoy bandits, since other

bandits could be perched high above ready to pounce. Every pre-flight

briefing carried the words: "Beware the Hun in the Sun."

These wise words were ignored one morning by another

Spitfire squadron and a fierce dog-fight occurred in which three Spits

and two 109's were downed. We were scrambled to give assistance but when

our twelve Spits with overheated engines reached the battle ground fifty

miles north of Malta, the sky was empty. Below five dinghies bobbed in

the water where friend and foe could be distinguished by the colour of

their one man rubber rafts. After an hour we were replaced by another

protecting squadron and returned to base. As we refuelled another

squadron was scrambled. From the nearby radio repair truck I heard the

leader's "Tally-Ho" and knew that another dog-fight was in progress.

Rapidly we were all refuelled and strapped into our cockpits ready to

take off. A third Spitfire squadron was hurled into the Mediterranean

sky prior to the return of the second wave. Only ten aircraft of the

second wave landed, so we knew that two more Spitfires had been lost.

The third wave returned intact at which time we were ordered aloft. On

arrival at the battle area, I peered unbelievingly at nine dinghies

bobbing in the water- four of ours and five of theirs. Whether by

instinct or orders, 'The Bull' placed us on a low patrol line west of

the rubber flotilla. In a moment, I spied and reported a dozen bandits

flying at our level two miles east. The Bull's voice barked: "Shut-up

Blue One!" I knew then he had already spotted the 109's. In complete

silence and in almost parade formation, we patroled our sentinel line to

the west whilst the enemy repeated our manoeuvre to the east.

After some time, a rescue boat from Sicily and

another from Malta arrived and began to fish out their respective downed

airmen. When the task was completed, we escorted our rescue craft back

to Malta and I could see the 109's were providing the same cover to

their boat. I smiled in my oxygen mask... As the news of our sortie

spread the airmen adopted the big grin of our leader's face. From that

moment on, even through the difficult winter months that lay ahead, the

morale of 417 Squadron members improved. This was the stimulant that was