|

Ilmari

Juutilainen

Interview by Jon Guttman,

Military History

An autographed photo of Ilmari Juutilainen in

the cockpit of Brewster BW-364 at Hirvas base 1942

In two wars, Ilmari Juutilainen and his fellow

pilots helped preserve their country's independence and taught the

Soviet Union a lesson: "If you threaten Finns, they do not become

frightened--they become angry. And they never surrender."

Ilmari Juutilainen scored more than 94 victories in two

wars, flying Fokker D.XXIs, Brewster B-239s and Messerschmitt Me-109Gs.

Neither Jossif Stalin nor Adolf Hitler regarded their

nonaggression pact of August 1939 as anything more than a postponement

of inevitable hostilities between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

After they had divided up Poland between themselves in September, Hitler

became embroiled in a war against Britain and France, while Stalin

grabbed what he considered strategic territories adjacent to Russia. One

concession Stalin sought was part of Finland's Karelian Isthmus on which

he wanted to build air and naval bases. (Stalin`s real plan was to

occupy the entire Finland just like the Baltic countries, see Edvard

Radzinski`s book "Stalin". FTA remark) When Finland refused to

give up her lands the Soviets bombed Helsinki and launched and invasion

on November 30, 1939.

The ensuing conflict, known as the Winter War, ended on

March 13, 1940, with the Soviet occupation of 10 percent of Finnish

land, but not before the Red Army had suffered several humiliating

defeats at the hands of the Finns. The Voyenno Vozdushny Sily

(Red Army air force, of VVS) had suffered even more disproportionate to

the outnumbered but highly skilled pilots of the Suomen Ilmavoimat

(the Finnish air force).

Epitomizing the elan and training that made the

Ilmavoimat so formidable was Eino Ilmari Juutilainen, whose 94

official victories made him the Finnish ace of aces. In an exclusive

interview with

Military History

editor Jon Guttman, "Illu" Juutilainen described his most notable

exploits during the Winter War and in the Continuation War, as Finland

called her participation in World War II as a co-belligerent rather than

a formal ally of Germany.

Military History: Could you tell us

about your pre-war background?

Juutilainen: I was born in Lieksa on February 21, 1914,

but I spent my childhood in Sortavala. As a

teenager I was a member of the Volunteer Maritime Defence Association

and we had a fine time sailing at the Laatokka Sea.

MH: What inspired you to take up

flying?

Juutilainen: There was an Ilmavoimat

base in the middle of our town, and it was a permanent source of

interest for all of us youngsters. Many of us became pilots later - for

example, my Winter War flight leader and Continuation War squadron

commander, Eino "Eikka" Luukkanen. One important inspiration was a book

about the Red Baron; Manfred von Richthofen, which my older brother gave

me. I remember sitting by the upstairs window, dreaming about aerial

manoeuvres. I began my national service as an assistant mechanic in the 1st Separate Maritime

Squadron from 1932 to 1933, then got a pilot's license in a civilian

course. I then joined the Ilmavoimat as a non-commissioned

officer and got my military pilot training in the Ilmasotakoulu (Air

Force Academy) at Kauhava from 1935 to 1936. I had the opportunity to

choose my first assignment, and on February 4, 1937, I went to LeLv

(Lentolaivue, or air squadron) 12 at Suur-Merijoki Air Base

near Viipuri. In 1938 I went to Utti Air Base and got one year of really

tough fighter flying and shooting. Then, on March 3, 1939, I was

assigned to LeLv 24, a fighter unit equipped with Dutch-built Fokker

D.XXIs, at Utti Air Base.

MH: What was training like in the

Ilmavoimat?

Juutilainen: The international trend in the early 1930's

was to use a tight, three-plane formation, or "vic", as a basic fighter

element. The fighter pilots in Finland knew that they would never get

large numbers of fighters , and they considered the large tight

formations ineffective. From studies conducted between 1934 - 1935, the

Ilmavoimat developed a loose two-plane section as the basic

fighter element. Divisions (four fighters) and flights (eight aircraft)

were made of loose sections, but always maintaining the independence of

the section. The distance between the fighters in the section was 150 -

200 meters, and the distance between sections in a division was 300 -

400 meters. The principle was always to attack, regardless of numbers;

that way the larger enemy formation was broken up and combat became a

sequence of section duels, in which the better pilots always won.

Finnish fighter training heavily emphasized the complete handling of the

fighter and shooting accuracy. Even basic training at the Air Force

Academy included a lot of aerobatics with all the basic combat

manoeuvres

and aerial gunnery.

MH: What were your feelings when the

war broke out on November 30, 1939?

Juutilainen: I was mentally ready, because the signs had

been so clear. Still, it was hard to believe that it was really true

when we took off on our first intercept mission. I think in general the

people were angry. We knew, of course, of Stalin's demands that we give

the Soviet Union certain areas to improve Leningrad's security. And our

answer was clear enough: No way! The nation's reaction to the war was

not analytical - it was emotional. The feeling was, "When I die, there

will be many enemies dying, too."

MH: What sort of preparation occurred?

Juutilainen: As the international situation worsened,

our defence forces started so-called extra exercises in early October

1939. All fighters and weapons were checked, more ammunition belts

loaded, and maintenance equipment and spare parts packed on the lorries

to be ready to move. On October 11 we flew from Utti to Immola Air Base,

which was nearer the border. Shelters were built for the fighters and we

kept flying combat air patrols - careful to stay on our side, so that we

didn't provoke the Soviets. The younger pilots got additional training

in aerial combat and gunnery. During bad weather we indulged in sports,

pistol shooting and discussions about fighter tactics. Our esprit de

corps was high despite the fact that we would be up against heavy odds.

We were ready.

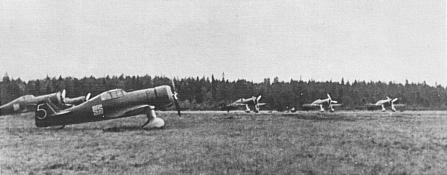

Fokkers at Immola Air Base, autumn 1939.

MH: What was the Fokker D.XXI like to

fly?

Juutilainen: It was our best fighter in 1939, but the

Soviet Polikarpov I-16 was faster, had better agility and also had

protective armour for the pilot. I flew later a war booty I-16, and it

did 215 knots at low level and turned around a dime. I liked that plane.

In comparison, the Fokker could make about 175. The D.XXI also lacked

armour, but it had good diving characteristics and it was a steady

shooting platform. I think that our gunnery training made the Fokker a

winner in the Winter War.

MH: Can you describe your first fight?

Juutilainen: December 19, 1939,

was the first real combat day after a long period of bad weather. I had

some trouble starting my engine, and so I got a little behind the rest

of my flight. When I was close to Antrea, I got a message of three enemy

bombers approaching. After about half a minute, I saw three Ilyushin

DB-3s approaching. I was about 1,500 feet above them and started the

attack turn just like in gunnery camp at Käkisalmi. The DB-3s

immediately dropped their bomb loads in the forest and turned back. I

shot the three rear gunners, one by one. Then I started to shoot the

engines. I followed them a long way and kept on shooting. One of them

nosed over and crashed. The two others were holed like cheese graters

but continued in a shallow, smoking descent. I had spent all of my

ammunition, so I turned back. There was no special feeling of real

combat. Everything went exactly like training.

Luukkanen, Juutilainen, Dahl, Alho and Fokker D.XXI

MH: What were the circumstances of your 1/6

shared victory on December 23?

Juutilainen: At that time, Soviet bombers flew

without fighter escort, and that was a typical situation when our

flight attacked a formation of Tupolev SB-2s. Several of us shot at

several targets, and the kills were then shared, because it was

impossible to distinguish a decisive attack. Later, I stopped

counting those shared cases and always gave my share to the younger

pilot.

On the right LLv 24 pilots: Lt. E. Luukkanen (front left),

Sgt. I. Juutilainen, Sgt. J. Dahl (on the wing) and Sgt. M. Alho.

MH: What about your first encounter

with an I-16 on December 31?

Juutilainen: That was a classic, old time aerial duel. I

was initially in a very good position behind that Red pilot, but he saw

me and started a hard left turn. I followed, shooting occasionally,

testing his nerves. Our speed decreased as we circled tightly under the

cloud deck, which was as low as 600 feet. My opponent's fighter was much

more agile than mine, and he was gradually gaining the advantage, so I

decided to pull a tactical trick on him. As he was getting into my rear

sector, I pulled into the cloud, continuing my hard left turn. Once

inside it, I rolled to the right and down, out of the cloud. I had

estimated right - I was again behind my opponent. When he next saw me, I

had already closed to a range of about 100 yards. He apparently decided

to outturn me, as he had done before. I put the sight on him and

squeezed the trigger. My tracers passed a few yards in front of him, and

I eased the stick pressure to adjust my aiming point. My next burst

struck his engine, which began to belch smoke. I continued firing,

letting the tracers walk along the fuselage. Then once more I pulled

hard, taking a proper deflection and shot again. There was a continuous

stream of black smoke as the target pitched over and went into the

forest.

MH: What other missions did you carry

out besides interception?

Juutilainen: Our reconnaissance aircraft were obsolete,

so they had to carry out their missions at night or in bad weather,

while we flew many daytime reconnaissance missions in our fighters. We

also occasionally carried out some ground-attack missions until the last

days of the war, when the enemy tried a flanking offensive over the ice

of the Gulf of Finland at Viipuri Bay. Those were decisive operations,

but for us fighter pilots they were also the most miserable missions of

the war, for the Soviets massed their fighters to cover the ground

troops. We could achieve surprise by using the weather conditions and

coming from different directions every time, quickly attacking over the

ice, then fighting our way back to base to rearm and refuel for a new

mission. During those missions, I personally fired some 25,000 rounds

into the Red Army.

MH: What were your feelings when

Finland was forced to accept Soviet terms in the end?

Juutilainen: I was disappointed. We had been able to

stop the Soviet offensive, they had gained only a limited land area, and

we had inflicted heavy losses on them. Thanks to small losses and

deliveries of new Gloster Gladiators, Fiat G.50s and Morane-Saulnier MS

406s, our fighter force was stronger than it had been at the beginning

of the war. We felt ourselves winners, but now we had to give them some

areas that were firmly in our hands. Later, when the economic situation

became clearer, the decision was more understandable. Sweden was

neutral, Germany was hostile and support from France and Britain proved

to be inadequate. Finland simply did not have enough resources to

continue a prolonged campaign alone. Ultimately, the important thing was

Finland's independence. We had been fighting to save that, and we had

indeed saved it. I think we also taught a lesson to Stalin and company:

If you threaten Finns, they do not become frightened - they become

angry. And they never surrender.

MH: What did you do between March 1940

and June 1941?

Juutilainen: At the end of March 1940 we flew from our

last wartime base, Lemi (which was on the ice of a lake) to Joroinen,

where our fighters were overhauled. Then we gave our Fokkers away and

began to familiarize ourselves with a new fighter, the Brewster B-239.

Some of those planes had already arrived in the last days of the Winter

War ( see Brewsters to

Finland), and now they were picked up from Trollhättan, Sweden,

where Norwegian mechanics were assembling them after sea transport.

American test pilot Robert Winston acted as his company's representative

in that process. The Brewsters were flown to Malmi Air Base near

Helsinki, and our squadron started to operate there. On June 14, 1940,

two Soviet bombers shot down one of our airliners over the Gulf of

Finland, shortly after it had taken off from Tallinn, Estonia. I was

searching for the plane with my Brewster, and I found a Soviet submarine

in the middle of aircraft debris, obviously looking for diplomatic mail.

In August 1940, we moved to a new base at Vesivehmaa, north of Lahti.

There, we tested the Brewster's performance and gunnery characteristics

and found both to be quite good. Many pilots put all their bullets in

the target. On June 17, we got and order to stay at the base, in

continuous readiness, so we guessed that we would be at war rather soon.

Fokkers at Joroinen ice base, April 1940

MH: What were your impressions of the

B-239?

Juutilainen: I started my Brewster flights in the

beginning of April 1940, doing all the aerobatics manoeuvres, stall and

dive tests. I was happy with my Brewster. It was agile, it had 4,5 hours

endurance, good weaponry - one 7,62 mm and three 12,7 machine guns - and

an armoured pilot's seat. It was so much better than the Fokker that it

was in another category. If we had had Brewsters during the Winter War,

the Russians would have been unable to fly over Finland. It was also a

"gentleman's travelling plane", for it had a roomy cockpit and room in

the fuselage, as we used to say, for a poker gang. We unofficially

transported mechanics, spare parts, oil canisters etc. in our Brewsters.

Once, though two pilots went a little too far - a flight sergeant was

flying, and in the fuselage was a second lieutenant, his friend, his dog

and a lot of baggage. Upon landing the plane went off the runway and the

suitcase came out. Both pilots were punished. Humorously, the

lieutenant's sentence started with: "As the commander of the crew of a

single-seat fighter.."

The unfortunate "Transport Brewster",

BW-354 at Immola October 15, 1942

|