Chuck Yeager's accomplishments as an ace in WWII have been overshadowed by his

achievements as a test pilot, but his fighter pilot experiences were remarkable

on their own. An eighteen-year old West Virginia country boy, he joined the U.S.

Army Air Force in 1941 and shot down eleven (and a half!) German planes,

including two Me-262 jets.

He was also shot down over France, evaded, joined the Maquis, and made his way

back to England via Spain. Somehow he persuaded the brass to let him continue

flying fighter missions in Europe, contrary to policy. All of this by the age of

twenty-two.

Born in 1923, son of Albert Hal Yeager (a staunch Republican, so firm in his

party loyalties that he once refused to shake President Harry Truman's hand),

Charles E. "Chuck" Yeager grew up in Myra, on the Mud River in West Virgina. His

dirt-poor youth was filled with hillbilly themes that sound romantic today, but

probably weren't much fun at the time: making moonshine, eating cornmeal mush

three times a day, shooting squirrels for dinner, chasing rats out of the

kitchen, going barefoot all summer, butchering hogs, and stealing watermelons.

At an early age Chuck could do well at anything requiring manual dexterity or

math: ping-pong, shooting, auto mechanics.

He enlisted in the Army Air Corps when he graduated from Hamlin High School in

1941, and became an airplane mechanic. He hated flying, after throwing up his

first time in the air. But when the chance came to become a "Flying Sergeant,"

with three stripes and no K.P., he applied, and was accepted. His good

coordination, mechanical abilities, and excellent memory enabled him to impress

his instructors in flight training.

357th Fighter Group

Assigned to the 363rd Fighter Squadron, of the 357th Fighter Group, he moved up

to P-39s with the squadron at Tonopah, Nevada. Unlike many other pilots, he

always liked the P-39 (which probably would have been a decent airplane if it

had had a turbocharger). Here at Tonopah, he first developed the fighter pilot's

detached attitude toward death, even getting angry at those he thought had died

needlessly or through lack of skill. During the ruthless weeding-out process at

Tonopah, the pilots worked as hard at playing as they did at flying. They

frequented the bars and cathouses of Tonopah and nearby Mina, until the sheriff

ran them out of the latter establishment. He and his lifelong friend, Bud

Anderson, both made it through the process.

When the squadron went to California to train for escort missions, Yeager drew

temporary duty at Wright Field, Ohio, testing new props for the P-39 and also

getting a chance to fly the big new P-47s. He took the opportunity to buzz his

hometown, less than an hour's flying time away. As Hamlin's only fighter pilot,

they knew who it was. He rejoined the squadron out in California, where he met

his future wife Glennis, "pretty as a movie star and making more money than I

was."

Next the squadron moved to Casper, Wyoming for more training. It was also great

hunting; one time Chuck went up in his P-39 and carefully herded a dozen

antelope toward a pre-arranged spot, where his armed ground confederates had a

field day. They ate antelope roasts for a month. But he almost "bought the farm"

in Wyoming. On October, 23, 1943, during a high speed exercise, his P-39's

engine blew up, the plane burst into flames, and Yeager had to bail out. He

survived, but was hospitalized with a fractured spine

The 357th FG shipped out for Europe in winter of 1943-44, and began operations

in February, 1944, the first P-51 equipped unit in the Eighth Air Force. Yeager

shot down his first Messerschmitt on his seventh mission (one of the early

Mustang missions over Berlin), and the next day, March 5, three FW-190s caught

him and shot him down. He bailed out over occupied France, being careful to

delay pulling his ripcord until he had fallen far enough to avoid getting

strafed by the German fighters.

He had landed about 50 miles east of Bordeaux, injured and bleeding, but armed

with a forty-five calibre pistol and determined to make his way over the

Pyrenees to Spain. He hid in the woods the first night, ate a stale chocolate

bar from his survival kit and huddled under this parachute. The next morning he

encountered a French woodcutter.

With the Resistance

They couldn't communicate very well, but the woodcutter whispered "Boche" and

gestured for Yeager to stay put. Uncertain as to the Frenchman's loyalties, but

having no better choices, Yeager stayed, but trained his gun on the path when a

he heard a couple people returning that night. "American, a friend is here come

out."

His new friends led him to a barn where he hid, while the Germans searched for

him. An English-speaking woman questioned him, and satisfied that he was not a

German 'plant', the local resistance people help him, starting with a local

doctor who removed the shrapnel from his leg. They took him to the nearest

maquis group, to hide out with them, until the snow had melted enough to permit

passage over the Pyrenees. The Maquis group, about 25 men, constantly kept on

the move, always being hunted by German Fieseler Storch observation planes.

Yeager was an outsider with the Maquis, and sometimes relations were strained,

but they accepted him when he was able to help fuse plastic explosives.

After exciting and freezing adventures, he made it over the mountains into

Spain. On March 30, 1944, he sat in the American consul's office. After he

languished in a Spanish hotel for six weeks, the U.S. government negotiated a

deal with the Franco government - a straight swap of six evadees for an amount

of Texaco gasoline. The other 357th pilots were shocked when Yeager appeared; he

was the first downed pilot to have returned.

Well-considered rules forbade the return of evaded pilots to combat; if they

were shot down a second time, they would be liable to reveal information about

the Resistance network to the German interrogators. But Chuck Yeager would have

none of it; he was determined to return to combat. The evadee rule was strict,

but Yeager and a bomber pilot named Fred Glover appealed all the way to General

Eisenhower, who promised to "do what he could." While the decision was pending,

the Group let Yeager fly training missions. Once they were called to cover a

downed pilot in the Channel, a Ju-88 appeared and Yeager couldn't restrain

himself from going after it, shooting it down at the German coast. He gave the

gun camera footage and the credit to another pilot, but still caught Hell.

Return to Combat

Ike decided to allow Yeager to return to combat in the summer of 1944, which he

did with a vengeance, now flying a P-51D nicknamed Glamorous Glen, gaudily

decorated in the red-and-yellow trim of the 357th. At first, the pickings were

slim, as the German fliers seemed to be laying low. He flew in a four plane

division with Bud Anderson and Don Bochkay, two other double aces. On September

18, he flew in support of the Market Garden glider drops over Arnhem, but

couldn't do much to stop the appalling slaughter of the C-47s. By this time, he

had been promoted to Lieutenant, a commissioned officer.

Yeager became an 'ace-in-a-day' on October 12, leading a bomber escort over

Bremen. As he closed in on one Bf-109, the pilot broke left and collided with

his wingman; both bailed out, giving Yeager credit for two victories without

firing a shot. In a sharp dogfight, Yeager's vision, flying skills, and gunnery

gave him three more quick kills.

The German Me-262 jets appeared in combat in late 1944, but went right after the

bombers, avoiding dogfights with the Mustangs. Whenever they wanted, they could

just open it up, and pull away from the P-51s with a 150 MPH speed advantage.

One day Yeager caught one on its approach to an airstrip. Flying through dense

flak, he downed the jet, and earned a DFC for the feat.

He flew his last "combat" mission in January, 14 1945. He and Bud Anderson

cooked up a scheme to sign on for the day's missions as "spares," and then do

some uninhibited flying. Anderson describes this, and other events in his

life-long friendship with Yeager, in his autobiography, To Fly and Fight:

We hit the Dutch coast, took a right and flew south, 500 across France into

Switzerland. Chuck was the guide. And I was the tourist.

We dropped our tanks on Mount Blanc and strafed them, trying to set them afire

(it seemed like a good idea at the time), then found Lake Annecy, and the

lakeshore hotel where Yeager and DePaolo had met. We buzzed the hotel, fast

enough and low enough to tug at the shingles, and then we zoomed over the water,

right on the deck, our props throwing up mist.

We'd just shot up a mountain in a neutral country, buzzed half of Europe, and

probably could have been court-martialed on any one of a half-dozen charges. It

didn't matter We were aglow. It was over, we had survived, we were finished, and

now we would go home together.

When we landed at Leiston, my crew chief jumped on my wing, "Group got more than

50 today. Must've been something. How many did you get?"

"None," I confessed in a small, strangled voice. I felt sick.

Chuck and Glennis were married in February, and he reported to Wright Field in

July, the start of his even more extraordinary career as a test pilot. He

impressed his instructors so much, that despite his non-com background and his

West Virginia accent, he was assigned to the XS-1 project at Muroc Field in

California.

Muroc Field

After WW2, Chuck Yeager was assigned to be a test pilot at Muroc Field in

California.

Muroc was high up in the California desert, a barren place except for sagebrush

and Joshua Trees. The main attraction of Muroc was Rogers Dry Lake, a flat

expanse that was covered with a couple inches of water in the winter, and dried

out hard and flat in the spring. A natural landing field, with miles of good

surface in every direction. In 1946, the whole place was off-limits, a top

secret Army base, developing jet and rocket planes. And there was almost nothing

there - two simple hangars, some fuel pumps, one concrete runway, and a few

shacks.

In many ways, Muroc was fighter pilot Heaven in the late '40s: the run-down,

Quonset-hut facilities didn't attract many visits from the Army Air Force top

brass, and there wasn't much to do there but fly, and drink and drive fast cars.

Pancho Barnes' "Fly Inn" was the pilots' favourite watering hole.

Breaking the Sound Barrier

One of the great unknowns of the time was the so-called "sound barrier." Planes

like the British Meteor jets that approached the speed of sound (760MPH at sea

level, 660 MPH at 40,000 feet) had encountered severe buffeting of the controls.

At that time, no one knew for sure whether an airplane could exceed "Mach 1,"

the speed of sound. A British pilot, Geoffrey de Havilland, had died trying. The

U.S. Army was determined to find out first.

The Army had developed a small, bullet-shaped aircraft, the Bell X-1, to

challenge the sound barrier. A civilian pilot, Slick Goodlin, had taken the Bell

X-1 to .7 Mach, when Yeager started to fly it. He pushed the small plane up to

.8, .85, and then to .9 Mach. The date of Oct. 14, 1947 was set for the attempt

to do Mach 1. Only a slight problem developed. Two nights before, after an

evening at Pancho's, Chuck and Glennis went out horseback riding, Chuck was

thrown, and broke two ribs on his right side. He couldn't have reported this to

the Army doctors; they might have given the flight to someone else. So Yeager

taped up his ribs and did his best to keep up appearances. On the day of the

flight, it became apparent that, with his injured right side, he wouldn't be

able to shut the door of the Bell X-1. In the plane's tiny cockpit; he could

only use his (useless) right hand. He confessed his problem to Ridley, the

flight engineer. In a stroke of genius, Ridley sawed off a short piece of

broomstick handle; using it with his left hand, Yeager was able to get enough

leverage to slam the door shut.

And that day, Chuck Yeager became the first man to fly faster than the speed of

sound. Tom Wolfe described the conclusion of the exhilarating flight in his

splendid book, The Right Stuff:

The X-1 had gone through "the sonic wall" without so much as a bump. As the

speed topped out at Mach 1.05, Yeager had the sensation of shooting straight

through the top of the sky. The sky turned a deep purple and all at once the

stars and the moon came out - the sun shone at the same time. ... He was simply

looking out into space. ... He was master of the sky. His was a king's solitude,

unique and inviolate, above the dome of the world. It would take him seven

minutes to glide back down and land at Muroc. He spent the time doing victory

rolls and wing-over-wing aerobatics while Roger Lake and the High Sierras spun

around below.

After the flight, the Army clamped tight security on the whole thing, and Yeager

couldn't tell anyone. He celebrated with just a few other pilots at Pancho's. He

flew a dozen more transonic flights in the X-1, but still under tight wraps. His

accomplishment wasn't announced to the public until mid-1948. The Bell X-1 is

now on display at the National Air and Space Museum

After the establishment of the Air Force as a separate branch of the military,

Muroc became Edwards Air Force Base.

Flight Test in the 1950's - The X-Planes

Because of his consummate piloting skill, his coolness under pressure and

ability to detect a problem, quickly analyze it and take appropriate action,

Yeager was selected to probe some of the most challenging unknowns of flight in

aircraft such as the X-1A, X-3, X-4, X-5 and XF-92A.

Douglas D-558-II Skyrocket

The records of the X-1 were soon exceeded by the swept-wing Douglas D-558-II

Skyrocket. First flown in February, 1948. Pilots such as Pete Everest, Bill

Bridgeman, and Marion Carl pushed the envelope with it, achieving speeds of Mach

1.45 and 1.88. Carl took it as high as 83,000 feet. But its ultimate performance

came in November, 1953, when Scott Crossfield reached Mach 2 in a shallow dive

at 62,000 feet.

X-1A

Crossfield's distinction as "the fastest man alive" was short-lived. Less than a

month later, Yeager piloted the rocket-powered X-1A to a record 1,650 mph (Mach

2.44) on Dec. 12, 1953. During this flight, he became the first pilot to

encounter inertia coupling. The aircraft literally tumbled about all three axes

as it plummeted for more than 40,000 feet before he was able to recover it to

level flight. Even his rival, Scott Crossfield, has since conceded that it was

"probably fortunate" that Yeager was the pilot on that flight "so we had the

airplane to fly another day." Later in 1953, Kit Murray flew the X-1A up to a

new record height, 90,440 feet. Only one model of the Bell X-1A existed; it was

destroyed in July, 1955

X-2

As flight researchers designed aircraft that could fly at Mach 3, they

encountered more problems: severe heating, instability, and worse inertial

coupling. The swept-wing Bell X-2, with a 15,000 pound thrust, dual chambered

rocket engine, constructed of stainless steel, was the next in the series to

meet these challenges. Pete Everest made the first powered flight in the X-2 in

November, 1955 and later flew it to a new speed record of Mach 2.87. In 1956

pilots Mel Apt and Iven Kincheloe (a Korean War ace) were assigned to the X-2

project. "Kinch" set a new altitude record of 126,000 feet on Sept. 7. Three

weeks later Mel Apt became the first man to reach Mach 3; he encountered the

same inertial coupling and tumbling as Yeager had in the X-1A, but couldn't pull

out of it. Both he and the aircraft were lost.

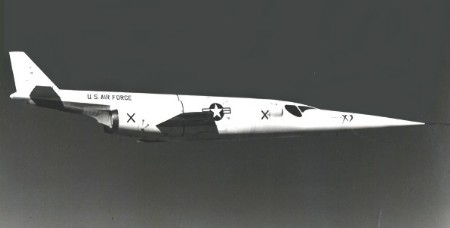

X-3

X-3

The Douglas X-3 looked like the hottest and faster airplane ever. It still does.

But looks are deceiving. Westinghouse proposed J46 turbojet engines grew too

large for the X-3. To get the plane airborne, a pair of J34's were installed,

but could never power the plane as intended for sustained supersonic flight

test. The X-3 could only exceed Mach 1 in a steep dive. Yeager flew the X-3.

X-15

Of course, the ultimate X-plane was the X-15, a true space plane, which pilots

like Bob White, Joe Engle, and Neil Armstrong took to extraordinary new records

in the 1960's. Joe Walker took the X-15 to a speed of Mach 5 in 1963.

By latter-day standards, it is remarkable that, while engaged in a wide range of

such highly experimental flight research programs, Yeager was also involved in

the evaluation of virtually all of the aircraft that were then being considered

for the Air Force's operational inventory. Indeed, he averaged more than 100

flying hours per month from 1947-1954 and, at one point, actually flew 27

different types and models of aircraft within the span of a single month.

In 1953, Yeager tested the Russian MiG-15, serial #2057, that a North Korean

pilot had defected with.

Command

Through the 1950's and 60's, Yeager continued his successful career as an Air

Force officer and test pilot.

In October 1954, he was assigned to command the 417th Fighter Squadron, first in

Germany and then in France. Returning to the United States in September 1957, he

served as commander of the 1st Fighter Squadron at George Air Force Base, Calif.

While he did not enter the astronaut program with John Glenn and the other

Mercury Seven, he was appointed director of the Aerospace Research Pilot School

(ARPS) at Edwards Air Force Base.

One of the planes he tested in 1963 was the NF-104, an F-104 with a rocket over

the tailpipe, an airplane which theoretically could climb to over 120,000 feet.

Yeager made the first three flights of the NF-104. On the fourth, he planned to

exceed the magic 100,000 foot level. He cut in the rocket boosters at 60,000

feet and it roared upwards. He gets up to 104,000 feet before trouble set in.

The NF-104's nose wouldn't go down. It went into a flat spin and tumbled down

uncontrollably. At 21,000 feet, Yeager desperately popped the tail parachute

rig, which briefly righted the attitude of the plane. But the nose promptly rose

back up and the NF-104 began spinning again. It was hopeless. At 7,000 feet

Yeager ejected. He got tangled up with his seat and leftover rocket fuel, which

burnt him horribly. He hit the ground in great pain and his face blackened and

burned, but standing upright with his chute rolled up and his helmet in his arm

when the rescue helicopter arrived.

This scene was dramatically presented toward the end of the movie, The Right

Stuff, and some have conflated this scene with Yeager breaking the sound barrier

in the X-1.

He went to Vietnam as commander of the 405th Fighter Wing in 1966 and flew 127

combat missions, and eventually rose to the rank of Brigadier General.

In February 1968, he took command of the 4th Tactical Fighter Wing at Seymour

Johnson Air Force Base, N.C., and in February 1968, led its deployment to Korea

during the Pueblo crisis. In July 1969, he became vice commander of the 17th Air

Force, at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, and then, in January 1971, he was assigned

as U.S. defence representative to Pakistan. On June 1, 1973, he commenced his

final active duty assignment as director of the AF Safety and Inspection Centre

at Norton Air Force Base, Calif. After a 34-year military career, he retired on

March 1, 1975. At the time of his retirement, he had flown more than 10,000

hours in more than 330 different types and models of aircraft.

In 1986, Yeager was appointed to the Presidential Commission investigating the

Challenger accident.